Script

Transmission of the alphabet to and within Italy

To Italy

In the 8th century BC, the island of Pithekoussai (modern Ischia) off the coast of Campania was colonized by Greeks from Euboia. While it is not quite clear whether the settlement was a proper colony or just a trading post, it spawned the foundation of historically important Kyme around the middle of the 8th century on mainland Italy. Pithekoussai itself seems to have lost importance at the turn of the century. The alphabet used by the colonists was that of the Euboic mother-cities Chalkis and Eretria. – Indeed, one of the oldest testimonies of early Greek writing is from Pithekoussai: the so-called Cup of Nestor, dated to the last quarter of the 8th century. (Jeffery 1990: 235) The Etruscans would have been in contact with the Greek settlers from the beginning, and the acquisition of their script was not a long time coming: The oldest document of written Etruscan, a kotyle from Tarquinia (Ta 3.1), is dated to about 700 (Wallace 2008: 17).

As the oldest Etruscan abecedarium on an ivory tablet from Marsiliana d’Albegna (ET: AV 9.1; about 650) shows, the Etruscans adopted the Greek alphabet, in its Eastern Greek "red" variety as used in Euboia, without any changes with regard to the different phonemic systems of the two languages. (For details see Jeffery 1990: 236 ff.) Only by and by do the documented abecedaria reflect a process of adaptation to writing practice. Etruscan had a plosive system consisting of two rows, written with the Greek characters for the unvoiced unaspirated (Pi, Tau, Kappa (/Gamma/Qoppa)) and unvoiced aspirated (Phi, Theta, Khi) rows. A phonetic realisation very much like the Greek is communis opinio among Etruscologists (see Wallace 2008: 30 f.). In any case, the obsolete characters for the mediae dropped out – all except Gamma, which together with Kappa and Qoppa became part of a curious orthographic rule for writing allophones, and only later replaced both the other characters as the exclusive one for the velar stop. Due to the lack of /o/ in Etruscan, Omikron fell away. In the 6th century, an additional sign ![]() was created for /f/, after a phase of writing the sound with a digraph <vh> or <hv>, and added to the end of the row. As concerns the writing of sibilants, a certain confusion on the part of the Greeks (see Jeffery 1990: 25 ff., Swiggers 1996: 266 f.) appears to have been propagated to the Etruscans: The Etruscan language seems to have had – apart from a dental affricate written with Zeta – two sibilants /s/ and probably /ʃ/ which were written with Sigma and San – in the South Sigma for /s/, San for /ʃ/, the other way round in the North. In the Southern cities Caere and Veii, where a number of divergences from general Etruscan writing practice can be observed over the course of time, a Sigma with more than three strokes appears instead of San. Finally in Cortona, a monophthongised, possibly long /e/ was consistently written with the character

was created for /f/, after a phase of writing the sound with a digraph <vh> or <hv>, and added to the end of the row. As concerns the writing of sibilants, a certain confusion on the part of the Greeks (see Jeffery 1990: 25 ff., Swiggers 1996: 266 f.) appears to have been propagated to the Etruscans: The Etruscan language seems to have had – apart from a dental affricate written with Zeta – two sibilants /s/ and probably /ʃ/ which were written with Sigma and San – in the South Sigma for /s/, San for /ʃ/, the other way round in the North. In the Southern cities Caere and Veii, where a number of divergences from general Etruscan writing practice can be observed over the course of time, a Sigma with more than three strokes appears instead of San. Finally in Cortona, a monophthongised, possibly long /e/ was consistently written with the character ![]() . As is customary in archaic Greek inscriptions, Etruscan inscriptions are generally sinistroverse, apart from a short phase around 600 in Caere and Veii. Unlike Greek practice, boustrophedon writing is rare. While word separation is consistently executed on Nestor's Cup, the archaic Etruscan texts often dispense with it, until it establishes itself in neo-Etruscan time (after 470). (For details see Wallace 2008: 17 ff.; a collection of Etruscan abecedaria in Pandolfini & Prosdocimi 1990: 19–94.)

. As is customary in archaic Greek inscriptions, Etruscan inscriptions are generally sinistroverse, apart from a short phase around 600 in Caere and Veii. Unlike Greek practice, boustrophedon writing is rare. While word separation is consistently executed on Nestor's Cup, the archaic Etruscan texts often dispense with it, until it establishes itself in neo-Etruscan time (after 470). (For details see Wallace 2008: 17 ff.; a collection of Etruscan abecedaria in Pandolfini & Prosdocimi 1990: 19–94.)

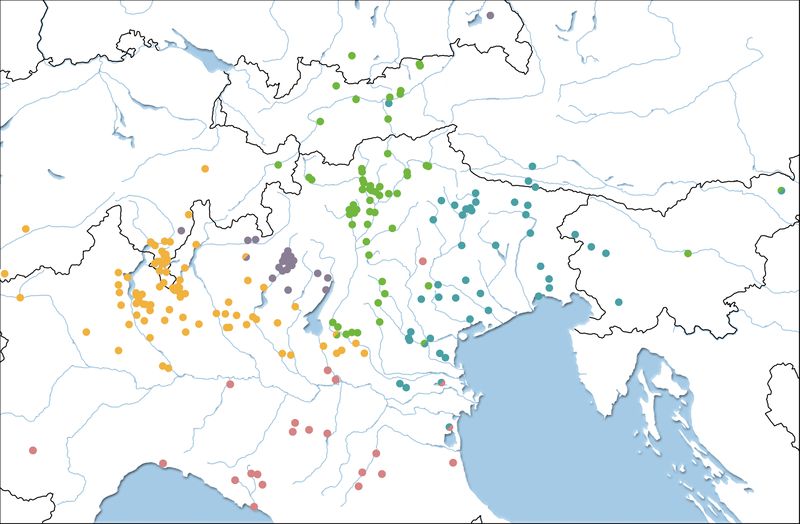

As things present themselves to us now, the Etruscan script has found its way to the peoples north of the river Po more than once, but not from the Etruscan settlements in Padania. Etruscan inscriptions in the very North (find places in pink on the map) are known from Liguria (Li), the Reggio Emilia and the area around Mantova (Pa), the environs of Bologna (ancient Felsina, Fe), and from Adria (Ad) and Spina (Sp). The oldest testimonies come from the Reno valley (Fe 2.1, Fe 3.1, Fe 6.1, Fe 2.2, Fe 2.3, from around 600) and from Rubiera (the stelae Pa 1.1 and 1.2, dated to the end of the 7th century). In both cases, the traditions only start again some hundred years later, i.e. at the end of the 6th century in Marzabotto, in the 5th century in the Reggio Emilia and Mantova. The great ports and commercial cities Adria and Spina only became relevant as Etruscan settlements around 500. A number of gravestones from Liguria, especially around the Magra river and its tributaries, are dated to the 2nd half of the 6th century; most of them are filed as being written in a North Italic alphabet in the Lexicon Leponticum (sigla MS and SP). For the question of whether the inscription(s) of Feltre (Pa 4.1) are linguistically and/or epigraphically Etruscan, see here.

Venetic

The Veneti are speakers of an Indo-European language settling in the Veneto (find places in blue on the map). Their inscriptions are collected in Pellegrini & Prosdocimi 1967; for supplementation see Prosdocimi 1988 and numerous publications by Anna Marinetti, esp. Marinetti 2004b. For the "traditional" view on the origin of the Venetic alphabet (from the Etruscan alphabets of Adria and Spina) see Pellegrini 1959. According to the more recent theory of Prosdocimi, a first, archaic version of the Venetic script ("phase 1"), attested securely only in one inscription (*Es 120, dated to the beginning of the 6th c. at the latest) and arguably in two further inscriptions (Es 1, *Es 122), was based on a model from Northern Etruria, while a separate tradition lies at the basis of most of the younger locally diverse alphabets (Este, Padua, Cadore, etc., "phase 2"). The archaic Venetic alphabet seems to have featured a rare form of Theta, ![]() , which is found in a handful of inscriptions from 6th-century Chiusi and Volsinii (Cl 2.8, Cl 2.6, Cl 2.5, Vs 1.23 and Vs 1.14, see Colonna 1972: 470), as seen in *Es 120. *Es 122 shows that the digraph <vh> was used to write /f/, rather than the new character

, which is found in a handful of inscriptions from 6th-century Chiusi and Volsinii (Cl 2.8, Cl 2.6, Cl 2.5, Vs 1.23 and Vs 1.14, see Colonna 1972: 470), as seen in *Es 120. *Es 122 shows that the digraph <vh> was used to write /f/, rather than the new character ![]() , which was introduced no sooner than the middle of the 6th century. The table shows the characters contained in the abovementioned inscriptions (disregarding minor variants). Pi is missing, but note that *Es 122 has

, which was introduced no sooner than the middle of the 6th century. The table shows the characters contained in the abovementioned inscriptions (disregarding minor variants). Pi is missing, but note that *Es 122 has ![]() , read l by Prosdocimi; cp. Pi in the form

, read l by Prosdocimi; cp. Pi in the form ![]() in Chiusi. Syllabic punctuation is absent.

in Chiusi. Syllabic punctuation is absent.

The younger alphabet of Este is unusually well documented on a number of votive writing tablets from a sanctuary-cum-writing school and distinguished by syllabic punctuation, both of which phenomena, together with the actual content of the inscriptions, connect it with the 6th century writing tradition of the Portonaccio sanctuary in Veii in the South of Etruria. The background of syllabic punctuation is debated.

Syllabic punctuation became the key feature of Venetic script, even though alphabet variants from other parts of the Venetic realm deviate from the Este alphabet, most prominently in the writing of the dental stops. Prosdocimi argues that the younger phase 2 alphabets represent different solutions for reconciling the archaic Venetic alphabet with the younger Etruscan one and particularly the theoretical grid on which the writing instruction was based. Whether the Veneti still had access to the characters for mediae (as lettres mortes through Etruscan teaching) is hard to judge, but they did not use them to write their voiced stops (Prosdocimi's considerations on p. 331 ff.). Instead, they employed the superfluous letters for the Etruscan aspirated row. While in the case of labials and velars, this transition appears to have happened smoothly (Pi = /p/, Phi = /b/; Kappa = /k/, Khi = /g/), the characters for the dentals were shifted around. *Es 120 clearly demonstrates the use of Tau for /d/; the abovementioned Chiusi-style Theta ![]() (

(![]() in Es 1 and *Es 122) must be expected to stand for /t/. This distribution is also documented for phase 2 Vicenza on a stela (Vi 2). In the younger Este alphabet (and also in the sanctuaries of Làgole (Calalzo di Cadore) and Auronzo di Cadore), /t/ as in the archaic inscriptions is written as a (large) St. Andrew's cross, but Zeta is employed to write /d/. A third combination is used in Padua, where first Etruscan Tau, later St. Andrew's cross are in use for /d/, while /t/ is written with a more traditional framed form of Theta

in Es 1 and *Es 122) must be expected to stand for /t/. This distribution is also documented for phase 2 Vicenza on a stela (Vi 2). In the younger Este alphabet (and also in the sanctuaries of Làgole (Calalzo di Cadore) and Auronzo di Cadore), /t/ as in the archaic inscriptions is written as a (large) St. Andrew's cross, but Zeta is employed to write /d/. A third combination is used in Padua, where first Etruscan Tau, later St. Andrew's cross are in use for /d/, while /t/ is written with a more traditional framed form of Theta ![]() (rounded or angular).

(rounded or angular).

The origin of St. Andrew's cross is somewhat obscure: Prosdocimi (p. 332), regarding the archaic distribution, explains Tau for /d/ and Theta for /t/ by a developing homography of ![]() and

and ![]() /

/ ![]() . The phonetic values were swapped before the characters were differentiated again, leading to

. The phonetic values were swapped before the characters were differentiated again, leading to ![]() being used for /t/ henceforth. He points to the Lepontic alphabet and the Este alphabet tablets for evidence of a tendency of Tau to tend towards a cross-shape. To further avoid homography in this area, Tau was substituted by Zeta in Este; in Padua, the form of Theta was changed to

being used for /t/ henceforth. He points to the Lepontic alphabet and the Este alphabet tablets for evidence of a tendency of Tau to tend towards a cross-shape. To further avoid homography in this area, Tau was substituted by Zeta in Este; in Padua, the form of Theta was changed to ![]() , which allowed Tau to turn into

, which allowed Tau to turn into ![]() . In other words, according to Prosdocimi,

. In other words, according to Prosdocimi, ![]() has two separate origins. On the Este writing tablets, where the letters can be unambiguously identified by their position in the row, Tau appears – with Prosdocimi: is retained as a lettre morte – in the shape of a cross, similar to, but clearly distinct from, Theta: While the latter is a large

has two separate origins. On the Este writing tablets, where the letters can be unambiguously identified by their position in the row, Tau appears – with Prosdocimi: is retained as a lettre morte – in the shape of a cross, similar to, but clearly distinct from, Theta: While the latter is a large ![]() , Tau is smaller and sometimes lopsided (e.g. in Es 23, see table). The individual letters being written in rectangular fields formed by a grid, with the grid lines regularly being used as hastae, it might be argued that the entire frame around the St. Andrew's cross representing Theta, whose tips reach into the corners of the field, is supposed to be part of the letter, forming a large, but otherwise inconspicuous

, Tau is smaller and sometimes lopsided (e.g. in Es 23, see table). The individual letters being written in rectangular fields formed by a grid, with the grid lines regularly being used as hastae, it might be argued that the entire frame around the St. Andrew's cross representing Theta, whose tips reach into the corners of the field, is supposed to be part of the letter, forming a large, but otherwise inconspicuous ![]() . Theta would then have come to be reduced to only the cross through reinterpretation. This explanation, however, predating Prosdocimis distinction of older and younger Venetic alphabet, does not account for the early appearance of

. Theta would then have come to be reduced to only the cross through reinterpretation. This explanation, however, predating Prosdocimis distinction of older and younger Venetic alphabet, does not account for the early appearance of ![]() and its apparent connection with Chiusi; note also that of six preserved tablets, a third (Es 24 and Vi 3) lack grid lines and yet feature Theta without a frame. On Es 25, where the grid lines are not used as parts of the letters, Theta is missing due to object damage, but the tablet serves to corroborate Prosdocimis theory by having Zeta in the place of Tau, probably due to a scribal error.

and its apparent connection with Chiusi; note also that of six preserved tablets, a third (Es 24 and Vi 3) lack grid lines and yet feature Theta without a frame. On Es 25, where the grid lines are not used as parts of the letters, Theta is missing due to object damage, but the tablet serves to corroborate Prosdocimis theory by having Zeta in the place of Tau, probably due to a scribal error.

The Venetic script features Omikron, which in the younger Este alphabet is situated not in its ancestral place, but at the very end of the row, as evidenced by the votive tablet Es 23, the only one bearing a complete row (in addition to the usual consonant-only). While Omikron is usually assumed to have been acquired directly from the Greek alphabet, probably through contact with Greeks settling in and south of the Po delta, Prosdocimi (p. 329) favours the theory that it was taken as a lettre morte (through writing instruction) from the Etruscan alphabet before its ultimate reduction. The Venetic use of Sigma vs. San follows the South Etruscan use, Sigma being the character used for the default sibilant and San leading a marginal existence. This is also the case in the archaic inscriptions; for possible explanations see Prosdocimi on p. 330 f. Finally, one of the distinctive features of the Venetic script is the frequent inversion of Lambda and Upsilon.

Cisalpine Celtic

Inscriptions in a Cisalpine Celtic language begin to appear in Western Transpadania around 600. The Lepontic core area lies between the Lago di Como and the Lago Maggiore; on the Celtic presence south of the Alps and the distinction between Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish see Uhlich 1999 and 2007. The inscriptions are collected in the Lexicon Leponticum, including all testimonies which may contain Celtic language material, as well as all inscription finds from west of the Adige even if ascription is dubious: A considerable number of documents, mostly short/fragmentary inscriptions of a low date, cannot be shown to be linguistically Celtic, or even to be written in the so-called Lugano alphabet (find places in yellow on the map). The "Lepontic" corpus being accordingly large and varied, it is hard to determine how the usual schibboleth characters – those for stops and fricatives – are used. Pi, Kappa and St. Andrew's cross are the standard letters, and can be shown to be used for both tenues and mediae. While Phi does not occur at all, Khi is employed for /g/ in one of the oldest inscriptions, as well as in three younger ones (TI·13, PV·4, VC·1.2) and in coin legends (NM·6.1, NM·6.1). In the latter, Khi appears together with Theta ![]() in the name Segetu or Segedu, which is also attested on four ceramic bowls from Prestino – here with Kappa for /g/ and Zeta

in the name Segetu or Segedu, which is also attested on four ceramic bowls from Prestino – here with Kappa for /g/ and Zeta ![]() for the dental. Theta appears two more times, in the shape

for the dental. Theta appears two more times, in the shape ![]() , in archaic VA·3 (possibly Etruscan) and the Inscription of Prestino. The latter, a lengthy inscription on a stela, is the only Lepontic text in which a systematic use of the characters for dentals can be observed: St. Andrew's cross is absent, Theta appears to stand for /t/. Tau in the shape

, in archaic VA·3 (possibly Etruscan) and the Inscription of Prestino. The latter, a lengthy inscription on a stela, is the only Lepontic text in which a systematic use of the characters for dentals can be observed: St. Andrew's cross is absent, Theta appears to stand for /t/. Tau in the shape ![]() demonstrably stands for /d/, while Zeta

demonstrably stands for /d/, while Zeta ![]() represents the affricate. Pi and Kappa are used for /p/ and /g/. Tau appears twice in later inscriptions (TI·36, NO·21.1), both times in the shape

represents the affricate. Pi and Kappa are used for /p/ and /g/. Tau appears twice in later inscriptions (TI·36, NO·21.1), both times in the shape ![]() , and both times together with St. Andrew's cross. While this strongly suggests that Lepontic St. Andrew's cross must, like its Venetic equivalent, be identified with Theta, the combined use of the two characters cannot be shown to be systematic (/t/ vs. /d/). Tau-, Zeta- and Khi-like shapes crop up a number of times in dubious and/or uninstructive contexts (see LexLep); another instance of lexical use of Zeta in NM·16. Beta, Delta and Gamma are absent until the appearance of Latin(oid) inscriptions from the Roman imperial time, but Omikron is present from the earliest inscriptions. On the use of San see LexLep and Stifter 2010.

, and both times together with St. Andrew's cross. While this strongly suggests that Lepontic St. Andrew's cross must, like its Venetic equivalent, be identified with Theta, the combined use of the two characters cannot be shown to be systematic (/t/ vs. /d/). Tau-, Zeta- and Khi-like shapes crop up a number of times in dubious and/or uninstructive contexts (see LexLep); another instance of lexical use of Zeta in NM·16. Beta, Delta and Gamma are absent until the appearance of Latin(oid) inscriptions from the Roman imperial time, but Omikron is present from the earliest inscriptions. On the use of San see LexLep and Stifter 2010.

Pi and Lambda are distinguished systematically as ![]() vs.

vs. ![]() ; Upsilon appears tip-down

; Upsilon appears tip-down ![]() , though inverted forms

, though inverted forms ![]() do occur. Alpha is closed (

do occur. Alpha is closed (![]() and similar) in the older inscriptions, later changing into

and similar) in the older inscriptions, later changing into ![]() . All in all, the Lugano alphabet is decidedly more similar to its Etruscan source than the Venetic. It is hard to determine whether individual inscriptions displaying divergent features are influenced by the Venetic writing tradition. The fact that both the Celtic and the Venetic languages are Indo-European may be the cause of parallel independent developments. Verger 1998 argues for a transmission of the alphabet to Western Transpadania via the area of Genova and the Scrivia valley. Note that a number of inscriptions from the area of La Spezia / Massa-Carrara displayed as Etruscan on the map are filed as linguistically and/or epigraphically Celtic / North Italic in the LexLep (sigla MS and SP).

. All in all, the Lugano alphabet is decidedly more similar to its Etruscan source than the Venetic. It is hard to determine whether individual inscriptions displaying divergent features are influenced by the Venetic writing tradition. The fact that both the Celtic and the Venetic languages are Indo-European may be the cause of parallel independent developments. Verger 1998 argues for a transmission of the alphabet to Western Transpadania via the area of Genova and the Scrivia valley. Note that a number of inscriptions from the area of La Spezia / Massa-Carrara displayed as Etruscan on the map are filed as linguistically and/or epigraphically Celtic / North Italic in the LexLep (sigla MS and SP).

Camunic

The corpus of the so-called Sondrio alphabet ("Camunic script“), conspicuous for its obvious graphic peculiarities, comprises the rock inscriptions of the Valcamonica, and a handful of testimonies from other places whose characters bear resemblance to those of the rock inscriptions, though the alphabets cannot be said to be identical (find places in grey on the map). Indeed, different systems seem to have been employed in the Valcamonica itself. The sigla system is not standardised, but useful collections are provided by Mancini 1980 and Tibiletti Bruno 1990. The language written in the rock inscriptions, called "Camunic" after the demonym Camunni documented by the ancients, has not yet been deciphered or convincingly connected to any of the surrounding languages; the other testimonies have been argued to write diverse languages: While the two inscriptions on stelae from Montagna in Valtellina (PID 252) and Tresivio (PID 253) feature endings similar to those commonly found in Camunic rock inscriptions, the non-Latin part of the Voltino bilingua has been read Etruscan as well as Raetic and Celtic. Celtic has also been suggested for the inscription on the Castaneda flagon, datable to the 5th–4th c. The dubious inscription AV-1, included in the TIR as linguistically Raetic, appears to be written in a variant of the Sondrio alphabet. Finally, the fragmentary inscription on a stela from Cividate Camuno in the Valcamonica itself is utterly enigmatic.

The main problem about the reading and interpretation of the inscriptions lies in the identification of the letters: Rock inscriptions from different localities, alphabetaria, and the (possibly idiosyncratic) testimonies from abroad appear to exhibit substantial differences in the use of some characters, which could so far be neither conclusively sorted out individually, nor reconciled. The picture presented by the twelve alphabetaria, or fragments of such (first edited in Tibiletti Bruno 1990; see also Tibiletti Bruno 1992), from the Valcamonica in particular demonstrates the Sondrio alphabet to be the odd one out among the North Italic alphabets. The table shows the characters as they appear in two distinct groups of alphabetaria: The first line gives the alphabet row PC 10 from Piancogno, with letters slightly standardised where their shape deviates from Camunic standard (Nu, Qoppa). The positions of Mu and Nu as well as of Gamma and Delta are interchanged in the original, Delta being written in ligature with Beta (sharing its last hasta). The ligature and possibly the inversion of the nasals also occur in the very similar row PC 27. The other alphabetaria or fragments of such from Piancogno are PC 6, PC 12 and probably PC 28. The second line gives an ideal alphabetarium from rock 24 of the Foppe di Nadro, based on FN 3, FN 4, FN 5 and FN 6, where only FN 3 and FN 6 are complete. Here also the nasals are interchanged. The two other alphabet fragments FN 1 and FN 2, also on rock 24, both end with Digamma (?) and display a variant form of Gamma ![]() . The presence of a complete Greek row suggests that the Sondrio alphabet came to Transpadania directly from a Greek source, without Etruscan mediacy. More than that, the Greek model can be argued not to have been of the "red" variety like the Euboic alphabet from which the other Italic alphabets ultimately derive. Even under such a premise, the shapes of the letters are highly unusual, not to mention the question of how such a script could have found its way into the remote Oglio valley.

. The presence of a complete Greek row suggests that the Sondrio alphabet came to Transpadania directly from a Greek source, without Etruscan mediacy. More than that, the Greek model can be argued not to have been of the "red" variety like the Euboic alphabet from which the other Italic alphabets ultimately derive. Even under such a premise, the shapes of the letters are highly unusual, not to mention the question of how such a script could have found its way into the remote Oglio valley.

There are two notable similarities between the Camunic and Raetic corpora, i.e. that both graphic variants of the Raetic special character appear in the context of the Sondrio alphabet: The character taking the position of San in PC alphabetaria is reminiscent of the Magré special character ![]() /

/ ![]() (but note that Magré has standard San); an arrow-shaped character like the Sanzeno special character

(but note that Magré has standard San); an arrow-shaped character like the Sanzeno special character ![]() appears in the problematic end sequences of the PC alphabetaria and on the Castaneda flagon.

appears in the problematic end sequences of the PC alphabetaria and on the Castaneda flagon.

Table

Map

The map below shows find places of inscriptions of the four North Italic corpora, together with Etruscan inscriptions in the Padan plain. It is intended to give a rough overview over the distribution areas, and glosses over problematic or ambiguous ascription in some cases (e.g., the "Ligurian" inscriptions). In the case of inscriptions which belong to different groups linguistically and alphabetically, the colours reflect the alphabet used (e.g., AV-1).

| Lepontic | Camunic | Raetic | Venetic | Etruscan |

Raetic script

The Raetic alphabets

Within the Raetic corpus, two different alphabets are distinguished. This goes back as far as Mommsen 1853 with his "Tyrolean" and "Verona" alphabets. Mommsen's "Tyrolean alphabet" was termed "Bozen alphabet" by Pauli 1885; his "Verona alphabet", originally attested in only one inscription, was rebranded as "Magrè alphabet" by Pellegrini 1918. After a suggestion by Mancini 1975: 306 (n. 42), the term "Bozen alphabet" was again changed to "Sanzeno alphabet" to reflect the latter site's large output of finds. (See Modern research on Raetic for details). Though the two alphabets had long been expected and were eventually demonstrated to encode the same language, the distinction still holds. The alphabets differ from each other in the use of graphic variants of a handful of letters, but share certain features which set them apart from the other North Italic alphabets and can therefore be considered typically Raetic.

| Pi | Lambda | Upsilon | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magrè alphabet | |||

| Sanzeno alphabet |

Pi, lambda and upsilon are the shibboleth characters which primarily distinguish the Magrè and Sanzeno alphabets (Whatmough 1933: 507; Prosdocimi 1971, 31–34). The Magrè alphabet employs forms which are identical with or similar to those used in the Venetic alphabets: pi with a pocket ![]() (sometimes opened

(sometimes opened ![]() or similar; the pocket is almost always open in Venetic, more similar to archaic Etruscan

or similar; the pocket is almost always open in Venetic, more similar to archaic Etruscan ![]() , which in Raetic is only attested once), lambda with a bar on top

, which in Raetic is only attested once), lambda with a bar on top ![]() , and tip-up upsilon

, and tip-up upsilon ![]() . The Sanzeno alphabet bears a closer resemblance to the Etruscan and Lepontic alphabets (Pauli 1885: 58–60): pi with a single bar

. The Sanzeno alphabet bears a closer resemblance to the Etruscan and Lepontic alphabets (Pauli 1885: 58–60): pi with a single bar ![]() , lambda with the bar at the bottom

, lambda with the bar at the bottom ![]() , and tip-down upsilon

, and tip-down upsilon ![]() correspond to the standard letter forms in those alphabets. According to Prosdocimi 1971: 33, the Venetic system of distinction is a variation of the archaic Etruscan one, while the Sanzeno forms (especially pi with a single bar) correspond to younger Etruscan ones. However, pi

correspond to the standard letter forms in those alphabets. According to Prosdocimi 1971: 33, the Venetic system of distinction is a variation of the archaic Etruscan one, while the Sanzeno forms (especially pi with a single bar) correspond to younger Etruscan ones. However, pi ![]() is already found in 7th-century Chiusi (e.g., Cl 2.1, 2.4).

is already found in 7th-century Chiusi (e.g., Cl 2.1, 2.4).

There is a certain extent of (random?) variation in the North Italic alphabets concerning the orientation of lambda and upsilon – non-inverted forms occur in the Venetic alphabetss (e.g., lambda ![]() in Es 16, upsilon

in Es 16, upsilon ![]() in Es 22); inverted forms, particularly of upsilon, appear sporadically in the Lepontic alphabet (e.g., TI·36.3). Pi appears with a single bar in Venetic inscriptions from the Cadore (e.g., Ca 65). Still, the variation in the Raetic inscriptions is too regular to be put down to chance. The only inscriptions in which Sanzeno-forms co-occur with Magrè-forms are three inscriptions from find places associated with the Magrè alphabet: AS-17.1 has hyper-distinctive

in Es 22); inverted forms, particularly of upsilon, appear sporadically in the Lepontic alphabet (e.g., TI·36.3). Pi appears with a single bar in Venetic inscriptions from the Cadore (e.g., Ca 65). Still, the variation in the Raetic inscriptions is too regular to be put down to chance. The only inscriptions in which Sanzeno-forms co-occur with Magrè-forms are three inscriptions from find places associated with the Magrè alphabet: AS-17.1 has hyper-distinctive ![]() next to

next to ![]() and

and ![]() , MA-6 has

, MA-6 has ![]() in combination with

in combination with ![]() . In the latter case, the occurrence of "incorrect" upsilon may be attributed to the tendency to invert letters (especially alpha and epsilon) which can be observed in the Magrè inscriptions (see below sub Writing direction). In VR-6, Magrè-type upsilon

. In the latter case, the occurrence of "incorrect" upsilon may be attributed to the tendency to invert letters (especially alpha and epsilon) which can be observed in the Magrè inscriptions (see below sub Writing direction). In VR-6, Magrè-type upsilon ![]() appears beside a character looking like the Sanzeno letter for the dental affricate

appears beside a character looking like the Sanzeno letter for the dental affricate ![]() ;

; ![]() is therefore ambiguous, as is tau

is therefore ambiguous, as is tau ![]() , which has its bar crossing the hasta, but is retrograde as typical for the Sanzeno alphabet (see T).

, which has its bar crossing the hasta, but is retrograde as typical for the Sanzeno alphabet (see T).

In addition to the above-mentioned letters, three others appear consistently in different graphic variants in the two alphabets. Tau always appears with the bar rising in writing direction, and usually not crossing the hasta, in Sanzeno-context (←![]() ; see T). Heta, though not common, always features three bars

; see T). Heta, though not common, always features three bars ![]() in Magrè-context, but two

in Magrè-context, but two ![]() in Sanzeno-context (single-bar

in Sanzeno-context (single-bar ![]() is as yet undocumented). Both alphabets have graphically innovative characters for the dental affricate:

is as yet undocumented). Both alphabets have graphically innovative characters for the dental affricate: ![]() in Sanzeno-context (not only at Sanzeno itself),

in Sanzeno-context (not only at Sanzeno itself), ![]() exclusively at Magrè (otherwise absent from Magrè-type inscriptions). See T on the question of whether the character

exclusively at Magrè (otherwise absent from Magrè-type inscriptions). See T on the question of whether the character ![]() is associated with the Magrè alphabet. Lastly, vestiges of Venetic syllabic punctuation are found only in Magrè-context, while word separation is only employed in Sanzeno-context (see below sub Writing direction).

is associated with the Magrè alphabet. Lastly, vestiges of Venetic syllabic punctuation are found only in Magrè-context, while word separation is only employed in Sanzeno-context (see below sub Writing direction).

While the forms of pi, lambda and upsilon as well as the instances of syllabic punctuation connect the Magrè alphabet with the Venetic alphabets, the Sanzeno alphabet has an Etruscan look to it. The similarities between the two alphabets concerning the use of the characters for obstruents, allegedly demonstrating a dependence on a Venetic model for both, is discussed below sub Obstruent spelling. The most evident feature unifying the Raetic alphabets is a negative one: the absence of omicron. Seeing that it is linguistically motivated (see The Raetic language), it does not provide a strong argument for a common model of the two alphabets. Purely graphic characteristics connecting the two are mu ![]() with only three bars instead of the more common four (

with only three bars instead of the more common four (![]() ), as well as two characteristics pertaining to writing direction: alpha ←

), as well as two characteristics pertaining to writing direction: alpha ←![]() with the bar slanting downwards against writing direction, and sigma ←

with the bar slanting downwards against writing direction, and sigma ←![]() with the upper angle opening against writing direction. Both the latter features are also known from neighbouring writing traditions – alpha is always retrograde in the Venetic inscriptions from the Isonzo region (Is 1–3, *Is 5–6); the orientation of sigma is notoriously irregular in all North Italic writing traditions – but they are significantly prevalent in the Magrè alphabet and good as exclusive in the Sanzeno alphabet.

with the upper angle opening against writing direction. Both the latter features are also known from neighbouring writing traditions – alpha is always retrograde in the Venetic inscriptions from the Isonzo region (Is 1–3, *Is 5–6); the orientation of sigma is notoriously irregular in all North Italic writing traditions – but they are significantly prevalent in the Magrè alphabet and good as exclusive in the Sanzeno alphabet.

The Sanzeno alphabet is distinguished by its uniformity across almost the entire time and area of its attestation. There is some minor variation in the forms of kappa (placement and length of bars ![]() ,

, ![]() ), rho (pointed vs. rounded pocket

), rho (pointed vs. rounded pocket ![]() ,

, ![]() ), tau (placement of bar

), tau (placement of bar ![]() ,

, ![]() ), phi (size of pockets

), phi (size of pockets ![]() ,

, ![]() ) and chi (placement and length of bars

) and chi (placement and length of bars ![]() ,

, ![]() ), but, otherwise, letter forms are quite stable. The character inventory, as far as can be seen, is the same in all find places. In contrast, we find a considerable range of regional and diachronic variation within the province of the Magrè alphabet, to an extent that the term "Magrè alphabet" should be regarded as more of a cover term for a number of local and chronological variants which share the features enumerated above, but exhibit differences with regard to individual letter forms, orthography, and (syllabic) punctuation:

), but, otherwise, letter forms are quite stable. The character inventory, as far as can be seen, is the same in all find places. In contrast, we find a considerable range of regional and diachronic variation within the province of the Magrè alphabet, to an extent that the term "Magrè alphabet" should be regarded as more of a cover term for a number of local and chronological variants which share the features enumerated above, but exhibit differences with regard to individual letter forms, orthography, and (syllabic) punctuation:

- a number of potentially archaic inscriptions exhibit different character sets and orthographies (see below sub Chronology),

- simplified syllabic punctuation is employed only at Serso and Magrè (see below sub Punctuation),

- the graphically and functionally obscure character

only appears at Serso and in a few scattered Magrè-type documents (see T),

only appears at Serso and in a few scattered Magrè-type documents (see T), - the Magrè alphabet's letter for the dental affricate

is only employed at Magrè (see Þ),

is only employed at Magrè (see Þ), - pi has a large pocket

in inscriptions from the Inntal (see P),

in inscriptions from the Inntal (see P), - zeta pops up sporadically and may denote a stop, Este-style, in some inscriptions (see Z), while

- zeta and san behave suspiciously in inscriptions from the area of Verona (see Z and Ś), and

- one of the two decidedly unlike petrograph alphabets attested in the Northern Limestone Alps shows some as yet unclassified idiosyncrasies (see Raetic epigraphy).

All these special features, however, are connected by their association with Venetic writing traditions.

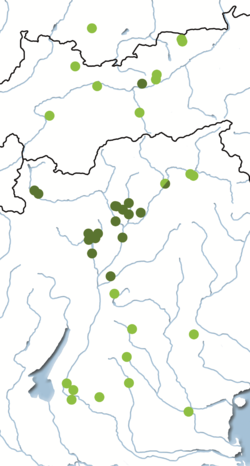

Distribution

The areas in which the Magrè and Sanzeno alphabets are used are neatly separated, as shown on the map on the right (Magrè-alphabet find places in light green, Sanzeno-alphabet find places in dark green). The Sanzeno alphabet is used in the central area, i.e. the Val di Non, the upper Adige valley (including the Unterland, the Bozen basin and the Vinschgau) and the Eisacktal, with tributary valleys and the surrounding highlands. Its area of distribution mostly coincides with the core area of the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture, i.e. Südtirol and the Trentino. Magrè-type inscriptions, as may be expected from their affinity with the Venetic script, come from the area of the archaeological Magrè group, i.e. the Alpine foothills south of Trento between Adige and Piave. This includes the inscriptions from the area of Verona, and the stray finds from the Padan plain (PA-1, TV-1). Contrary to what is generally asserted in the literature, inscriptions from beyond Brixen are also written in the Magrè alphabet. Tip-up upsilon ![]() appears in WE-4, IT-4, IT-2 and FP-1. The graphically ambiguous

appears in WE-4, IT-4, IT-2 and FP-1. The graphically ambiguous ![]() can be clearly identified as Magrè-type lambda rather than Sanzeno pi in WE-1 and WE-4 thanks to the well attested words lavise and eluku; a reading of the letter as lambda is also preferable in IT-7 and especially IT-4, where it is part of the pertinentive ending -le.

can be clearly identified as Magrè-type lambda rather than Sanzeno pi in WE-1 and WE-4 thanks to the well attested words lavise and eluku; a reading of the letter as lambda is also preferable in IT-7 and especially IT-4, where it is part of the pertinentive ending -le. ![]() being lambda, the associated pi with a pocket can be found in FP-1, IT-4 (which thus has the full set of diagnostic letters) and IT-8. In the latter two inscriptions, pi appears in a peculiar form

being lambda, the associated pi with a pocket can be found in FP-1, IT-4 (which thus has the full set of diagnostic letters) and IT-8. In the latter two inscriptions, pi appears in a peculiar form ![]() with a large angle which reaches the bottom of the line (see P). See ST-2 for another possible instance of

with a large angle which reaches the bottom of the line (see P). See ST-2 for another possible instance of ![]() , and Raetic epigraphy on the generally Venetoid letter forms and orthographic behaviour in the petrographs. Tau is

, and Raetic epigraphy on the generally Venetoid letter forms and orthographic behaviour in the petrographs. Tau is ![]() in WE-4; heta is absent, as is a specific character for the dental affricate (which does not appear in any Magrè-type inscriptions except in those from Magrè itself). Clear syllabic punctuation is absent, but see below sub Punctuation on puncts in certain petrographs.

in WE-4; heta is absent, as is a specific character for the dental affricate (which does not appear in any Magrè-type inscriptions except in those from Magrè itself). Clear syllabic punctuation is absent, but see below sub Punctuation on puncts in certain petrographs.

In the boundary areas between the two alphabet provinces, we often find mixed features, though – as said above – never within the same inscription. Two inscriptions from the south-eastern border of the Sanzeno-alphabet area, however, combine Sanzeno-type letter forms with what appears to be Venetoid syllabic punctuation (see below sub Punctuation): CE-1.3 from the valley of the Avisio (all five sequences on the Situla di Cembra are written in the Sanzeno alphabet with ![]() ,

, ![]() and consistent ←

and consistent ←![]() and ←

and ←![]() ), and SR-2 from the Valsugana (with

), and SR-2 from the Valsugana (with ![]() , not accompanied by pi or lambda). The Serso antlers, from a find place which still belongs to the core area of the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture, generally make up a somewhat varied group, though with some notable shared features. With the exception of problematic SR-2, the inscriptions are basically written in the Magrè alphabet; seven of the twelve feature some sort of punctuation, three of these have punctuated letters. Three of the inscriptions contain the letter

, not accompanied by pi or lambda). The Serso antlers, from a find place which still belongs to the core area of the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture, generally make up a somewhat varied group, though with some notable shared features. With the exception of problematic SR-2, the inscriptions are basically written in the Magrè alphabet; seven of the twelve feature some sort of punctuation, three of these have punctuated letters. Three of the inscriptions contain the letter ![]() , which also appears sporadically in the Val di Non and is suspect of belonging to an archaic tradition (see T).

, which also appears sporadically in the Val di Non and is suspect of belonging to an archaic tradition (see T).

The northernmost Sanzeno-alphabet inscription WE-3 and the southernmost Magrè-alphabet inscription in the Wipptal WE-4 both come from Stufels (Brixen). The Wipptal lies outside the reach of the Sanzeno alphabet, which may account for the fact that the Pustertal, which opens into the valley of the Eisack at Brixen, takes part in both traditions: PU-1 has Magrè-type letter forms, but displays a number of peculiarities, while PU-5, PU-6 and PU-11 have Sanzeno-style upsilon. This border at Brixen is not random, cf. Lunz 1981b: 43, who considers it as a point of transition between the northern and southern Alpine area (beside the Alpine divide at the Brenner pass), as it marks the point where the narrow Wipptal opens into the comparatively easily accessible Brixen basin.

Only one inscription breaks the pattern of distribution: IT-5, found in the Inntal, is clearly written in the Sanzeno alphabet. In light of a Venetic inscription found at the same site (*It 1), IT-5 is best judged as an import or the work of a travelling dedicant.

As concerns the inscribed Negau helmets, both found far from the Raetic area (not on the map), one bears at least one Sanzeno-alphabet inscription; the other one's inscription lacks the diagnostic letters, but features ![]() . The single fragmentary inscription from the Unterengadin (EN-1, not on the map), is too short to be ascribed to either of the alphabets.

. The single fragmentary inscription from the Unterengadin (EN-1, not on the map), is too short to be ascribed to either of the alphabets.

See Property:alphabet for a scalable and tagged map.

Chronology

From the overview given on Archaeology in the Raetic area, a rough history of Raetic writing culture can be inferred. However, it has to be taken cum grano salis as long as substantial and important finds such as the Magrè and Inn valley inscriptions cannot be included.

It can be observed that the oldest testimonies of Raetic writing, as said above, are notable for both inscriptions and supports, though it should not be forgotten that the Paletta di Padova and the Spada di Verona may be younger. Still, it appears that in a first phase of Raetic writing, only special objects were inscribed, sporadically and with much care. HU-7, PA-1 and VR-3 are apparently of votive character, containing the word utiku. The alphabets used differ from each other, only those of HU-7 and VR-3 may be compared: They both feature Magrè-style inverted ![]() and

and ![]() , though in regard to their age and possible status as "proto-Raetic" testimonies, it may be preferable not to assign them to the Magrè alphabet. However, there are typically Raetic features in three-bar Mu

, though in regard to their age and possible status as "proto-Raetic" testimonies, it may be preferable not to assign them to the Magrè alphabet. However, there are typically Raetic features in three-bar Mu ![]() and HU-7's →

and HU-7's →![]() , and notably

, and notably ![]() (in the absence of either Pi or Theta/(regular) Tau). PA-1 shares the inverted letters, but otherwise appears to work with a restricted character set, spelling utiku with

(in the absence of either Pi or Theta/(regular) Tau). PA-1 shares the inverted letters, but otherwise appears to work with a restricted character set, spelling utiku with ![]() and possible using a digraph <kh> for a marked velar. It employs punctuation for auslauting consonants (?). Phi, Tau and Chi are not employed in any of the three inscriptions. PU-1 is epigraphically notably different: While Upsilon and Lambda (here together with angled Pi) are also inverted, the alphabet used has Phi and Chi, and appears to employ a curious variant of Zeta

and possible using a digraph <kh> for a marked velar. It employs punctuation for auslauting consonants (?). Phi, Tau and Chi are not employed in any of the three inscriptions. PU-1 is epigraphically notably different: While Upsilon and Lambda (here together with angled Pi) are also inverted, the alphabet used has Phi and Chi, and appears to employ a curious variant of Zeta ![]() for a marked dental stop (i.e. in place of Tau). Also in evidence are four-stroke Sigma

for a marked dental stop (i.e. in place of Tau). Also in evidence are four-stroke Sigma ![]() , which occurs elsewhere only the more peculiar type of prevalently dextroverse Raetic rock inscriptions, and double-pennon San

, which occurs elsewhere only the more peculiar type of prevalently dextroverse Raetic rock inscriptions, and double-pennon San ![]() , isolated in the Raetic corpus.

, isolated in the Raetic corpus.

The oldest document from the central Raetic area, from the burnt-offerings site at the Monte Ozol, is reminiscent in form (![]() ) and content (terisna) not of the Sanzeno-type material discussed in the next paragraph, but of the Serso inscriptions and SL-1.

) and content (terisna) not of the Sanzeno-type material discussed in the next paragraph, but of the Serso inscriptions and SL-1.

In view of the fact that all the datable material from the central Raetic area (Sanzeno and the Nonsberg / Val di Non, Bozen / Bolzano), excepting the pottery, which only bears marks, comes from the 5th–4th c., it may tentatively be assumed that the writing culture emanating (allegedly) from the Sanzeno sanctuary flourished in these two centuries and constitutes a second phase of Raetic writing. Again, though, it has to be remembered that the bulk of the material is undated. If the use of the Sanzeno alphabet is indeed restricted to La Tène A and B, IT-5 can be argued to be by far the earliest document from the Inn valley.

At about the same time, San Briccio produces testimonies in the far South. Note that VR-1, featuring ![]() , points back towards VR-3, whereas VR-2 shows similarities to the young inscription groups of San Giorgio di Valpolicella and Castelrotto, which can be argued to connect the area of Verona with Etruscan writing (see above). The Montorio Veronese inscriptions, chronologically and geographically in between, fail to constitute a link.

, points back towards VR-3, whereas VR-2 shows similarities to the young inscription groups of San Giorgio di Valpolicella and Castelrotto, which can be argued to connect the area of Verona with Etruscan writing (see above). The Montorio Veronese inscriptions, chronologically and geographically in between, fail to constitute a link.

The inscriptions on the Situla Giovanelli in the 4th c., with their lack of the Sanzeno special character and solitary syllabic punctuation mark, constitute a smooth transition – at least on paper – to a conceivable third phase of Raetic writing, marked by discrete group finds mainly in the South: Bostel, Trissino, the abovementioned Montorio Veronese and San Giorgio di Valpolicella, as well as, a belated sign of life from the Sanzeno alphabet, the Ganglegg. It is understandable why the Serso and Magrè groups are generally preferred to be dated to this phase, though note that the Serso inscriptions may be as old as the 5th c. – the higher dating is suggested by arguably archaic ![]() .

.

The inscriptions from St. Lorenzen / San Lorenzo di Sebato as well as WE-4 and WE-1 from the Wipp- and Eisacktal, written in a Magrè-style alphabet similar to the oldest testimonies, show that a Venetoid writing tradition continued also in the North (outside the Sanzeno catchment area) during phase 2, which we have associated with the central Raetic area. The material from the Inn valley being mostly undated, it is hard to judge the progress of Raetic writing culture in the North. Note that IT-4 is dated by context and may be considerably older than the 1st c. The alphabet used in some of the rock inscriptions (see below) can be compared to that used in PU-1, indicating that the rock inscriptions themselves may be of considerable age.

When talking about the dating of Raetic inscriptions, the usual caveats apply: archaeo-logical dating on the basis of excavation context and typology is sometimes uncertain, and time frames of different extent make it hard to establish a chronology even where datings are available. Particularly in the Raetic corpus, we have a great number of old findings which cannot be dated, because their archaeological context is unknown. When dating an object through context, it must be observed that objects which have a short life span, such as ceramics, are likely to date from about the time which is determined by that context, whereas objects with a longer life span (especially if they are valuable), such as fibulas, may be considerably older (Gamper 2006, 43). Moreover, the time of production or even use of an object does not necessarily determine the time when the inscription was applied. A date for production or widespread use of objects gives a terminus post quem; a date for a grave or deposit gives a terminus ante quem (Schumacher 2004, 246; MLR, 10). The following paragraphs give an overview of the dating of objects with Raetic inscriptions which is strictly based on the archaeological data as presented in the literature. The possibility of dating inscriptions based on palaeography will be addressed in ch. 2.5.2. The oldest objects bearing Raetic inscriptions appear to be two of the more remarkable items in the Raetic corpus: the Situla in Providence and the Paletta di Padova. The situla with the inscription HU-7 is dated to the third quarter of the 6th c. on the basis of typology (Frey 1962, 46) . Unfortunately, the find place of the vessel is unknown, it having emerged from the Italian art market. In the museum’s announcement of the situla in 1934, the Etruscan necropolis at the Certosa di Bologna was given as find place, but the reliabil-ity of this statement was already qualified by Frey 1962, 1. The fact that a similar object – the Situla Certosa – was found there can either support the claim or challenge it (in that it makes the necropolis a plausible find place to make up for a decorated situla). The find place of the ritual spatula which bears the inscription PA-1 is known quite precisely, as it was found during excavations in a courtyard of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio in Padova, but no Bronze- or Iron-Age context came with it. The piece is dated typologically to the 6th– 5th c. (Gambacurta et al. 2002, 186 [no. 20]). The testimonies are similar insofar as the objects are atypical (the situla being the most elaborately decorated one in the Raetic corpus), and come from places to the south(-east) of the Raetic area proper, which have not yielded any other Raetic inscriptions: Bologna was Etruscan, Padova was a Venetic site. The so-called Spada with the inscription VR-3 – definitely not a sword – is dated to the 6th–5th c. by Marinetti 1987, 138 f. (n. 5), following Salzani’s (1984, 793) identification of the object as a skewer of the sort which was used in ritual feasts and his comparison of the piece to similar ones from Padova and Magdalenska gora. Salzani himself, however, gives the early 4th c., to which the Slovenian specimen can be dated by context (Salzani 1984, 181; also Gambacurta et al. 2002, 185 [no. 19]). De Marinis 1988, 121 lists the Spada among inscribed objects dated to the 5th c. The find place is indicated as Ca’ dei Cavri, a fraction of Bussolengo, in the original publication (Rossi 1672, 404 [“Campagna Caudina”]); if this is accurate, VR-3 is the only Raetic inscription find from the right bank of the Adige in the area of Verona. Some of the above-mentioned characteristics are shared by the Lothen belt plaque (inscription PU-1), which can be dated typologically to the 5th c. by its figural decorations – two deer – which are known from the iconographic programme of situlae (Lunz 1981a, 22). No other inscriptions are known from the Burgkofel, but there are finds from the immediate vicinity of St. Lorenzen. The settlement on the Steger hill, whence come three bones (inscriptions PU-5–7) and three potsherds (inscriptions PU-8–10), is dated princip-ally to the 5th–4th c. by Constantini 2002, 41, though individual finds may be younger. The settlement on the Sonnenburger Weinleite, which yielded a stone plaque with inscription PU-4 and a loom weight with marks, is dated to the 5th–3rd c. (ibid., 48); another loom weight comes from the Puenland settlement, dated to the 5th–4th c. (ibid., 22). The oldest document from the Raetic core area between Trento and the Bozen basin appears to be NO-13 on an astragalos from the Ciaslir on the Monte Ozol, the only high-altitude site to yield Raetic inscriptions. The place was in use, originally and probably throughout, as a burnt-offerings site from the late Bronze to the early Iron Age, possibly even into Roman times; highly diverse finds in combination with nearby fundaments of buildings make further interpretation difficult (Gleirscher et al. 2002, 247 [no. 133]). According to Perini 2002, 767, the inscription find comes from a layer dated to Retico A (middle of the 6th–middle of the 5th c.). The material from Sanzeno is difficult to interpret and date. Of the seven find spots, only the northernmost, Casalini, has demonstrably yielded inscribed objects, most im-portantly the bronzes, which were found by chance in a sand pit in the late 1940s. While the other find spots, dated to Retico A, testify to a large settlement (for an overview see Gamper 2006, 334–337 and Marzatico 2001, 496–501), the function of the excavated buildings (case retiche) at Casalini, dated to Retico B–C (LT A–B), is unclear – they are arranged in neat lines, sharing walls, as if planned out (Marzatico 2001, 496). A projected settlement is a possibility, even though a settlement clearly lay just to the south: the Casalini site may have been a replacement. One may also consider an emporion with rows of studios and shops (in light of the numerours iron finds) or, like Gleirscher et al. 2002, 251 (no. 155), a temple district with treasuries (regarding the votive objects). Nothdurfter 2002, 1136 thinks of cult buildings with bothroi in the basement and space for attaching votive gifts to the walls on the upper storey, together with administrative buildings and workshops which produced the votives. See also Marzatico 2001, 494 f. on the question of indoor sanctuaries. The large number of finds, many of them old findings without a precise context, is yet to be systematically reviewed in its entirety. The oldest document from Sanzeno which can be dated independently of its context is SZ-16 on the warrior statuette, dated typologically to the second half of the 5th c. (Walde-Psenner 1983, 108 [no. 85]). The half-plastic votive bronzes, which are typical for the Raetic area and therefore difficult to date through comparison with models from the south (Gleirscher et al. 2002, 207), are still likely to belong in the context of Etruscan-style bronze votives and to be from the same time or not much younger. Gempeler 1976, 51 f. argues for the 4th–3rd c. (specifically for the horse bronzes with SZ-9 and 14, and HU-5 and 6) with regard to Venetic and Etruscan influences (also Dal Rì 1987, 174 f. [no. 722 and 723] and De Marinis 1988, 122). Gleirscher apud Schumacher 2004, 247 (and impicitly in Gleirscher et al. 2002, 207) gives the 5th–4th c. He points to the fact that that the bronze with SZ-14 – the Cavaliere di Sanzeno – features a rider who wears a Negau helmet and to the similarity of the bronze with inscription SZ-3 with the more securely datable Dercolo bronze (see below). The bronze pieces with inscriptions SZ-87 and SZ-96 can also be compared with pieces included in the Dercolo hoard. Following the common dating of situlae, the situlae (SZ-30 situla and SZ-82 cist) and situla handles (with SZ-17, SZ-19 and SZ-31) can be dated typologically to the 5th–4th c. The iron helmet with SZ-73 is datable to LT A/B1 through typology (Nothdurfter 1992, 56). Nothdurfter 1979, 97–103 dates most of the iron material with marks to between the 5th and the end of the 2nd c., the phase which is thought to be the time in which the settlement flourished. The bulk of the pottery appears to belong in the later phase, the prominent Sanzeno bowls being dated to the 3rd–2nd c. (Marzatico 2001, 511, but see Gamper 2006, 13–17 about the issues of bowl chronology). The youngest inscribed object from Sanzeno is a Roman Imperial Age iron knife (in-scription SZ-38; Nothdurfter 1979, Beilage 2). The major sanctuary of Valemporga (Meclo) was in use from the late Bronze to the late Roman Imperial Age, with a bulk of finds from Retico A demonstrating an increased frequency in the early La Tène period. The stratigraphy being destroyed, individual finds can only be dated through typology (Gleirscher et al. 2002, 236). The miniature shield with inscription NO-3 and the fragment of a bronze-plaque figure with inscription NO-19, both from the sanctuary, are the only two inscribed specimens of the typical bronze plaque votives which belong in the context of situla art and are dated to LT A–B1 (Tschurtschen-thaler & Wein 1998, 243; Gleirscher et al. 2002, 205 f.; Marzatico 2012, 320–324), though a later date cannot be excluded (Gehring 1976, 161). The fragment of a situla with inscript-ion/mark NO-8 may be assumed to belong in the same time frame. The neighbouring site of the Campi Neri south of Cles, also a sanctuary with an even longer duration (Gleirscher et al. 2002, 236 [no. 81]), yielded a number of bronze objects, none of which can be securely dated. The bronze baton with inscription NO-15 can be compared with similar objects from the Dercolo hoard; the horse bronze with inscription NO-16, which was found together with the baton in a pit, can only contingently be compared to the Sanzeno bronzes, as it is worked in full-plastic (cf. the horse statuette with SZ-71), yet rather crudely made. The strainer with inscription NO-2 dates to around the birth of Christ (Gleirscher apud Schumacher 2004, 248). The slab from Tavòn with inscription NO-10, a stray find, cannot be dated. Most of the find places of inscriptions in the Val di Non are situated in the northern part of the valley. The only outlier is the more southerly Dercolo, where a hoard find of unclear function (Schindler 1998, 222–224. 232 f.) contained the horse-headed bronze with inscription NO-11. The hoard was deposited around 400 (Lunz 1974, 83; Schindler 1998, 231); seeing that the objects deposited in the situla appear to have been comparatively new (Schindler 1998, 231), the bronze may be dated to the late 5th c. Two unassociated Sanzeno bowls are younger (LT C–D; Schindler 1998, 224). The Fritzens bowl sherd with the marks NO-14, an old finding from somewhere in the Val di Non, dates from the 5th–3rd c. based on typology. The valley of the Adige between Salurn and Meran and the immediately adjoining mountainous areas have yielded a fair number of inscribed objects. While many finds come from well researched archaeological contexts, no homogenous group finds of inscriptions like the Sanzeno bronzes have so far been made in the area. The oldest settlement complex in the area was situated on the east side of the Mitterberg, facing the Adige, southeast of modern Pfatten in the Unterland. It yielded the oldest object in the corpus, a bronze Hallstatt-age axe from a hoard found above the grave field (Lunz 1974, 211 f.), dated to the 7th or early 6th c. (Marzatico 1997, 453). Like many of its kind, the bronze axe bears marks, but these are not Raetic characters; the testimony of BZ-17 has no bearing upon the chronology of Raetic script. The associated grave field of Stadlhof dates from the Hallstatt to the early La Tène period; the fragment of a cist with inscription BZ-11 from grave XVIII (Ghislanzoni 1939, 514 f.) and the slab with inscription BZ-10.1 from grave A (Franz 1951, 130) must therefore be dated to LT A or B. For the bronze key with inscription BZ-12, possibly from the potential bothros near the Leuchtenburg (Gleirscher et al. 2002, 261 [no. 198]), no dating is available. The potsherd with inscription BZ-13 from the settlement of Laimburg may be younger (3rd–2nd c.; Schumacher 2004, 211). Finally, the precise find spot of the fragmentary miniature vessel with inscription BZ-25, a museum find, is unknown, but the votive situlae belong typologically with the miniature shields and bronze plaque figures, and are, like these, well represented in the Meclo sanctuary. Four inscribed objects come from Überetsch. The only sporadically excavated site on the Putzer Gschleier west of St. Pauls near Eppan yielded three finds (none from the casa retica), which cannot be dated. The inscribed slab from Maderneid (Eppan) with inscript-ion BZ-24 can be dated to the Late Roman Republican period by the style of its decoration (Stefan Demetz p.c.). The area in the Bozen basin between the Bozen district of Moritzing and Siebeneich in the west is called the “sacred corner” (Heiliger Winkel/Sacro angolo) for the numerous find spots (see Tecchiati 2002); unfortunately, it has not so far been systematically ex-cavated. Four finds from the Moritzing grave field come not from excavated contexts, but from chance finds in the 19th c. Two – a situla handle with inscription BZ-9 and a fragment of a bronze vessel with inscription BZ-4 – are from a grave context dated to the second half of the 5th–first half of the 4th c. (Steiner 2002, 258) ; two cists with marks come from a context dated to the 4th–early 3rd c. (ibid., 254). On the dating of the helmet hoard found on the Kosman property (Jenesien; inscriptions BZ-26 to BZ-29) see below. The handle of a cist with inscription BZ-5, found during one of the minor excavations on the Greifen-steiner Hang, can be dated typologically to the 5th–3rd c. through typology (Lunz 1985, 145); the handle of a simpulum with inscription BZ-3, an old finding from the area of the Großkarnell property, is dated by typology to the 5th–4rd c. Further up the Adige valley, the bronze axe with inscription BZ-2, a stray find from the vicinity of the church St. Christoph near Tisens, is dated typologically to the 5th c. (Zemmer-Plank et al. 1985, 165 [no. 34]). The three potsherds with marks from the settle-ment of St. Hippolyt near Tisens and the iron sickle from the hilltop can not be securely dated, but the ceramics partly bear resemblance to material from the nearby sanctuary on the Hochbichl near Meran, which appears to be no younger than LT A–B (Lunz 1974, 193). A single antler piece with inscription VN-1 comes from the Tartscher Bichl near the place where the Münstertal meets the Adige valley. The major settlement appears to have been most important during the early and middle La Tène period, but must be expected to have been in use until LT C2, when it was essentially replaced by the Ganglegg settlement (Gamper 2006, 290 f.). The latter site, situated somewhat to the south on the northern flank of the valley, had already been settled in Ha D/LT A, and appears to have been constructed within a rather short time at the end of the 2nd c. and abandoned again just as suddenly at the end of LT D (ibid., 254). Among numerous perforated bones and bone needles of un-clear (original) function which were found on the floors of houses and apparently deposit-ed there during the ritual abandonment are numerous pieces with marks and some with inscriptions (VN-2–19). No inscription finds come from the Münstertal, and only one from the Engadin: the potsherd with inscription EN-1 from Suotchastè near Ardez is dated to LT A–B through context and typology (Caduff 2007, 16). The ceramics from the sanctuary on the Pillerhöhe near Fliess, of which three pieces bear inscriptions or script-like marks (IT-8–10), date to the early La Tène period (Tschurtschenthaler & Wein 1998, 247). To my knowledge, no datings are available for the settlement on the Hörtenberg near Pfaffenhofen. The Demlfeld sanctuary, part of a larger complex around Ampass, was in use throughout the younger Iron Age, but no precise dating is known for the bronze plaque with inscription IT-5. The settlement on the Himmelreich near Volders in the Inntal yields a great number of pot-sherds bearing marks (including IT-2) which are dated to the middle and late La Tène period (Gamper 2006, 265 f.). The carved antler with inscription IT-4 comes from house 2 of the Pirchboden settlement near Fritzens; the house was destroyed by fire in the late Iron Age, possibly in the course of the Roman Alpine campaign (Tomedi 2001, 32).

Writing of dentals

Writing direction

About three quarters of Raetic inscriptions whose writing direction can be determined are sinistroverse, the rest is dextroverse. Dextroverse inscriptions occur more frequently on rocks, as well as in Magrè. Real boustrophedon writing, i.e. the lines of one inscription being written alternately running towards the right and the left, is not attested, but a handful of inscriptions are written in so-called reverse boustrophedon, which means that all lines have the same orientation, but are inverted in relation to each other (e.g. WE-3). For a few inscriptions it can be demonstrated that the writer changed the way they held the object during the application of the characters, which lead to a change in writing direction. This implies that the choice of writing direction was not something that a user of Raetic writing regarded as important. On the other hand, single letters turned against writing direction are rare. Where they do occur, it is most usually Alpha or Sigma.

Word separation and syllabic punctuation

Word separation by punctuation mark is only employed in a handful of inscriptions from Sanzeno context (SZ-30, NO-3, NO-10, BZ-3, BZ-26, SL-2.1), using one to (most often) three vertically arranged dots or short vertical lines. PU-1 would be the only Magrè-alphabet inscription with separators, but the existence of the respective scratches is highly doubtful. A space is used to separate words on some of the Sanzeno bronzes (SZ-1.1, SZ-2.1, SZ-2.2, SZ-4.1, SZ-11), as well as in other inscriptions from Sanzeno context (BZ-10.1, BZ-12, CE-1.3, CE-1.5), and once in Magrè (MA-1). See also Non-script notational systems on para-script elements in inscriptions from the Vinschgau.

Apart from the space in MA-1, word separation does not exist in inscriptions from Magrè context. Instead, syllabic punctuation is employed in some subcorpora. The practice of syllable punctuation is a speciality of Venetic writing, where the rules are highly complex and the letters are usually marked on both sides (for details see Prosdocimi 1988: 336 ff.). In Raetic inscriptions (as indeed in some marginal Venetic traditions), the rules appear to have been somewhat relaxed – for example, isolated vowels in the beginning of inscriptions are not punctuated, and neither are the second elements of diphthongs. In the same vein, the letters are marked with a single punct placed behind (or inside) it.

- Serso: SR-4, SR-6, SR-7 and SR-10 have correct punctuation according to the supposed Raetic rules. For example: SR-6 a ru se θa r· na te ri s· na. It is not sure that SR-1 has punctuation at all, but note the similarity with the fragmentary SR-7. If line 1 is punctated, the punct is situated before rather than after Mu. In line 2, note that the not-punctuation of Khi would be in line with the Venetic special rules for consonant clusters (kv being one of the clusters which is not punctuated). On the status of s as the first element of clusters, see below. SR-8 also has a dubious element, but the punctuation of final s is correct. In SR-2, the punct appears to mark the genitive ending rather than a phonetically determined element (see below).

- Magrè: All of the five (or six) inscriptions with syllabic punctuation can be argued to be correctly executed. MA-14 is exemplary, as is MA-17 according to the Venetic rule excluding clusters whose second element is l (here kle). In MA-16, the dubious element resembling Phi must be treated as

. MA-12 and MA-13 are correct if clusters with s as first element (here st/sθ) are assumed to be exempt from punctuation, which is not in line with the Venetic rules, but phonetically apprehensible. Finally, in MA-6, the punct after final s in line 2, if it is intentional, is the only punct necessary in the entire inscription, the cluster θr being covered by the Venetic rules of exception.

. MA-12 and MA-13 are correct if clusters with s as first element (here st/sθ) are assumed to be exempt from punctuation, which is not in line with the Venetic rules, but phonetically apprehensible. Finally, in MA-6, the punct after final s in line 2, if it is intentional, is the only punct necessary in the entire inscription, the cluster θr being covered by the Venetic rules of exception. - In the petrographs, the situation is more complex. ST-4 is punctuated correctly according to the rules deductible from the Serso and Magrè inscriptions. In ST-5, ST-6 and AK-1.11, on the other hand, what appears to be marked is not phonetically, but grammatically determined elements, most strikingly the suffixes of the syntagma -nu-ale. In fact, considering that the letters of the suffix -nu are in the present cases written in ligature, the puncts might even advert to that. While the punct in ST-6 sa?al·esta- may well be a word separator (if estanuale is connected with estua(le)), those in ST-5 ker·akve and AK-1.11 ker·anu- might be either word separators or suffix markers, and ST-5 (h)e·stula- would even qualify as syllabic punctuation. The single punct in ST-8 might be any of the three.

- In the area of Verona, we find a number of inscriptions where puncts in the shape of short verticals, often in the upper or lower area of the line rather than in the middle, appear not so much to mark bothersome consonants, but to replace vowels (VR-2, VR-4, VR-10, VR-11, VR-14). Whether this phenomenon is linguistical or graphical is unclear. VR-17 seems to display syllabic punctuation according to Venetic rules (with marked i in a diphthong), which together with its four-barred Mu indicates Venetic writing. See also VR-6.

- Currently incomprehensible punctuation practices were employed on the Ganglegg and in Trissino, where a number of inscriptions, some of dubious linguistic relevance, are gayly punctuated without obvious signification. In VN-11, at least, the puncts appear to separate the inscription per se from para-script elements.

- Isloated finds with potential syllabic punctuation are TV-1.1 (highly irregular), CE-1.3 (correct syllabic punctuation), and PA-1 (probably the same), for which see the inscription pages.

In two inscriptions (IT-5, RN-2), the text is written into a grid. For delimitation signs, see Non-script notational systems.

![]() grid lines (2);

grid lines (2);

![]() word separation (

word separation (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ) (6);

) (6);

![]() word separation or syllabic punctuation (

word separation or syllabic punctuation (![]() ,

, ![]() ) (23);

) (23);

![]() syllabic punctuation (

syllabic punctuation (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ) (7);

) (7);

![]() ligatures with punct (11);

ligatures with punct (11);

![]() space (20)

space (20)

Ligatures

Ligatures are rare in Raetic, but considering that none (to our knowledge) are known from Venetic and Lepontic inscriptions, they might almost be considered a speciality of Raetic. We know both actual ligatures of letters, and inscribed punctuation marks (which are treated as ligatures in TIR).

Inscribed punctuation marks are exclusively syllabic puncts (as opposed to word separators). The practice is well known from Venetic, e.g. ???. In Raetic, they occur in the inscriptions of Magrè (MA-12, MA-13, MA-14, MA-16, MA-17) and Serso (SR-1, SR-6, SR-7, SR-10) as well as in PA-1 and possibly TV-1.1. The letters into which puncts are inscribed are Mu ![]() , Lambda

, Lambda ![]() and Rho

and Rho ![]() ; the punct can be either a dot

; the punct can be either a dot ![]() or a short stroke

or a short stroke ![]() . In the cases of

. In the cases of ![]() and

and ![]() , the punct is essentially just placed under the bar(s) of the letter, which must not necessarily be considered an inscribed punct, but may in some cases simply be due to space-saving or chance.

, the punct is essentially just placed under the bar(s) of the letter, which must not necessarily be considered an inscribed punct, but may in some cases simply be due to space-saving or chance. ![]() being attested at both Magrè and Serso,

being attested at both Magrè and Serso, ![]() and

and ![]() are also filed as ligatures in TIR. As concerns the two isolated inscriptions, they both have only

are also filed as ligatures in TIR. As concerns the two isolated inscriptions, they both have only ![]() – while in PA-1 the punct seems quite deliberately placed inside the angle formed by hasta and bar, its position in TV-1.1 is probably accidental (

– while in PA-1 the punct seems quite deliberately placed inside the angle formed by hasta and bar, its position in TV-1.1 is probably accidental (![]() is twice followed by a punct in the inscription rather than having it inscribed).

is twice followed by a punct in the inscription rather than having it inscribed).

Ligatures of letters occur in the petrographs of Steinberg and maybe Achenkirch, and in the Non valley. ST-5 and ST-6 both have an element ![]() = inverted and turned Nu

= inverted and turned Nu ![]() + Upsilon

+ Upsilon ![]() writing nu, more precisely the patronymic suffix -nu. In AK-1.11, the reading is doubtful. (See also AK-1.17 for another possible ligature.) It is not clear why just these two letters should be ligated, as other consecutive pairs of letters in the mentioned inscriptions would lend themselves to being combined in the same manner, i.e. the bars of the first letter being attached against writing direction to the hasta of the second one. The same is true for the ligature

writing nu, more precisely the patronymic suffix -nu. In AK-1.11, the reading is doubtful. (See also AK-1.17 for another possible ligature.) It is not clear why just these two letters should be ligated, as other consecutive pairs of letters in the mentioned inscriptions would lend themselves to being combined in the same manner, i.e. the bars of the first letter being attached against writing direction to the hasta of the second one. The same is true for the ligature ![]() = turned Lambda

= turned Lambda ![]() + Tau

+ Tau ![]() writing lt, attested only once in NO-3. The manner of forming the ligature is the same, and again there are other letter pairs in the inscription which might well be ligated in the same way.

writing lt, attested only once in NO-3. The manner of forming the ligature is the same, and again there are other letter pairs in the inscription which might well be ligated in the same way.

![]() NU ligature (1);

NU ligature (1);

![]() LT ligature (1);

LT ligature (1);

![]() ligatures with punct (11)

ligatures with punct (11)

Note that Marchesini reads ligatures with inverted Alpha in VR-2 (MLR 45) and VR-6 (MLR 291), and a ligature of Pi and Sigma in VR-13 (MLR 123). These are ad hoc-readings of epigraphically difficult inscriptions without linguistical rationale, and are therefore at this point not filed in TIR.

Bibliography

| AIF I | Carl Pauli, Altitalische Forschungen. Band 1: Die Inschriften nordetruskischen Alphabets, Leipzig: 1885. |

|---|---|

| Colonna 1972 | Giovanni Colonna, "Clusium et Orvieto", Studi Etruschi 40 (1972), 470–471. |

| ET | Helmut Rix, Gerhard Meiser (Eds), Etruskische Texte. Editio Minor [= ScriptOralia 23-24; Reihe A, Altertumswissenschaftliche Reihe 6-7], Tübingen: Gunter Narr 1991. (2 volumes) |

| Gamper 2006 | Peter Gamper, Die latènezeitliche Besiedlung am Ganglegg in Südtirol. Neue Forschungen zur Fritzens-Sanzeno-Kultur [= Internationale Archäologie 91], Rahden/Westfalen: Leidorf 2006. |