Script

Transmission of the alphabet to and within Italy

To Italy

In the 8th century BC, the island of Pithekoussai (modern Ischia) off the coast of Campania was colonized by Greeks from Euboia. While it is not quite clear whether the settlement was a proper colony or just a trading post, it spawned the foundation of historically important Kyme around the middle of the 8th century on mainland Italy. Pithekoussai itself seems to have lost importance at the turn of the century. The alphabet used by the colonists was that of the Euboic mother-cities Chalkis und Eretria – indeed, one of the oldest testimonies of early Greek writing is from Pithekoussai: the so-called Cup of Nestor, dated to the last quarter of the 8th century. (Jeffery 1990: 235) The Etruscans would have been in contact with the Greek settlers from the beginning, and the acquisition of their script was not a long time coming: The oldest document of written Etruscan, a kotyle from Tarquinia (Ta 3.1), is dated to about 700 (Wallace 2008: 17).

As the oldest Etruscan abecedarium on an ivory tablet from Marsiliana d’Albegna (ET: AV 9.1; about 650) shows, the Etruscans adopted the Greek alphabet, in its Eastern Greek "red" variety as used in Euboia, without any changes with regard to the different phonemic systems of the two languages. (For details see Jeffery 1990: 236 ff.) Only by and by do the documented abecedaria reflect a process of adaptation to writing practice. Etruscan had a plosive system consisting of two rows, written with the Greek characters for the unvoiced unaspirated (Pi, Tau, Kappa (/Gamma/Qoppa)) and unvoiced aspirated (Phi, Theta, Khi) rows. A phonetic realisation very much like the Greek is communis opinio among Etruscologists (see Wallace 2008: 30 f.). In any case, the obsolete characters for the mediae dropped out – all exept Gamma, which together with Kappa and Qoppa became part of a curious orthographic rule for writing allophones, and only later replaced both the other characters as the exclusive one for the velar stop. Due to the lack of /o/ in Etruscan, Omikron fell away. In the 6th century, an additional sign ![]() was created for /f/, after a phase of writing the sound with a digraph <vh> oder <hv>, and added to the end of the row. As concerns the writing of sibilants, a certain confusion on the part of the Greeks (see Jeffery 1990: 25 ff., Swiggers 1996: 266 f.) appears to have been propagated to the Etruscans: The Etruscan language seems to have had – apart from a dental affricate written with Zeta – two sibilants /s/ and probably /ʃ/ which were written with Sigma and San – in the South Sigma for /s/, San for /ʃ/, the other way round in the North. In the Southern cities Caere und Veii, where a number of divergences from general Etruscan writing practice can be observed over the course of time, a Sigma with more than three strokes appears instead of San. Finally in Cortona, a monophthongised, possibly long /e/ was consistently written with the character

was created for /f/, after a phase of writing the sound with a digraph <vh> oder <hv>, and added to the end of the row. As concerns the writing of sibilants, a certain confusion on the part of the Greeks (see Jeffery 1990: 25 ff., Swiggers 1996: 266 f.) appears to have been propagated to the Etruscans: The Etruscan language seems to have had – apart from a dental affricate written with Zeta – two sibilants /s/ and probably /ʃ/ which were written with Sigma and San – in the South Sigma for /s/, San for /ʃ/, the other way round in the North. In the Southern cities Caere und Veii, where a number of divergences from general Etruscan writing practice can be observed over the course of time, a Sigma with more than three strokes appears instead of San. Finally in Cortona, a monophthongised, possibly long /e/ was consistently written with the character ![]() . As is customary in archaic Greek inscriptions, Etruscan inscriptions are generally sinistroverse, apart from a short phase around 600 in Caere and Veii. Unlike Greek practice, boustrophedon writing is rare. While word separation is consistently executed on Nestor's Cup, the archaic Etruscan texts often dispense with it, until it establishes itself in neo-Etruscan time (after 470). (For details see Wallace 2008: 17 ff.; a collection of Etruscan abecedaria in Pandolfini & Prosdocimi 1990: 19–94.)

. As is customary in archaic Greek inscriptions, Etruscan inscriptions are generally sinistroverse, apart from a short phase around 600 in Caere and Veii. Unlike Greek practice, boustrophedon writing is rare. While word separation is consistently executed on Nestor's Cup, the archaic Etruscan texts often dispense with it, until it establishes itself in neo-Etruscan time (after 470). (For details see Wallace 2008: 17 ff.; a collection of Etruscan abecedaria in Pandolfini & Prosdocimi 1990: 19–94.)

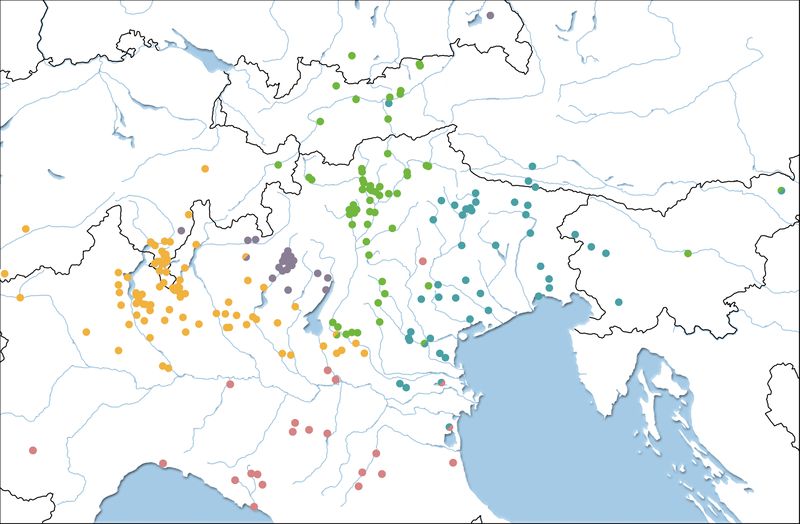

As things present themselves to us now, the Etruscan script has found its way to the peoples north of the river Po more than once, but not from the Etruscan settlements in Padania. Etruscan inscriptions in the very North (find places in pink on the map) are known from Liguria (Li), the Reggio Emilia and the area around Mantova (Pa), the environs of Bologna (ancient Felsina, Fe), and from Adria (Ad) and Spina (Sp). Inscriptions in the Reno valley start at the end of the 6th century (in Marzobotto); Fe 2.3, Fe 2.1. The great ports and commercial cities Adria and Spina only became relevant as Etruscan settlements around 500; the Reggio Emilia and Mantova also yield inscriptions only from the 5th century onwards – excepting the stelae Pa 1.1 and 1.2 from Rubiera, dated to the end of the 7th century. A number of gravestones from Liguria, especially around the Magra river and its tributaries, are dated to the 2nd half of the 6th century; most of them are filed as being written in a North Italic alphabet in the Lexicon Leponticum (siglae MS and SP). For the question of whether the inscription(s) of Feltre (Pa 4.1) are linguistically and/or epigraphically Etruscan, see here.

Eastern Transpadania

Venetic

The Veneti are speakers of an Indo-European language settling in the Veneto (find places in blue on the map). Their inscriptions are collected in Pellegrini & Prosdocimi 1967; for supplementation see Prosdocimi 1988 and numerous publications by Anna Marinetti, esp. Marinetti 2004b. For the "traditional" view on the origin of the Venetic alphabet (from the Etruscan alphabets of Adria and Spina) see Pellegrini 1959. According to the more recent theory of Prosdocimi, a first, archaic version of the Venetic script ("phase 1"), attested securely only in one inscription (*Es 120, dated to the beginning of the 6th c. at the latest) and arguably in two further inscriptions (Es 1, *Es 122), was based on a model from Northern Etruria, while a separate tradition lies at the basis of most of the younger locally diverse alphabets (Este, Padua, Cadore, etc., "phase 2"). The archaic Venetic alphabet seems to have featured a rare form of Theta, ![]() , which is found in a handful of inscriptions from 6th-century Chiusi and Volsinii (Cl 2.8, Cl 2.6, Cl 2.5, Vs 1.23 and Vs 1.14, see Colonna 1972: 470), as seen in *Es 120. *Es 122 shows that the digraph <vh> was used to write /f/, rather than the new character

, which is found in a handful of inscriptions from 6th-century Chiusi and Volsinii (Cl 2.8, Cl 2.6, Cl 2.5, Vs 1.23 and Vs 1.14, see Colonna 1972: 470), as seen in *Es 120. *Es 122 shows that the digraph <vh> was used to write /f/, rather than the new character ![]() , which was introduced no sooner than the middle of the 6th century (tabelle). The table shows the characters contained in the abovementioned inscriptions (disregarding minor variants). Pi is missing, but note that *Es 122 has

, which was introduced no sooner than the middle of the 6th century (tabelle). The table shows the characters contained in the abovementioned inscriptions (disregarding minor variants). Pi is missing, but note that *Es 122 has ![]() , read l by Prosdocimi; cp. Pi in the form

, read l by Prosdocimi; cp. Pi in the form ![]() in Chiusi. Syllabic punctuation is absent.

in Chiusi. Syllabic punctuation is absent.

The younger alphabet of Este is unusually well documented on a number of votive writing tablets from a sanctuary-cum-writing school and distinguished by syllabic punctuation, both of which phenomena, together with the actual content of the inscriptions, connect it with the 6th century writing tradition of the Portonaccio sanctuary in Veii in the South of Etruria. The background of syllabic punctuation is debated. History of syllabic writing (Kyme).

Syllabic punctuation became the key feature of Venetic script, even though alphabet variants from other parts of the Venetic realm deviate from the Este alphabet, most prominently in the writing of the dental stops. Prosdocimi argues that the younger phase 2 alphabets represent different solutions for reconciling the archaic Venetic alphabet with the younger Etruscan one and particularly the theoretical grid on which the writing instruction was based. Whether the Veneti still had access to the characters for mediae (as lettres mortes through Etruscan teaching) is hard to judge, but they did not use them to write their voiced stops (Prosdocimi's considerations on p. 331 ff.). Instead, they employed the superfluous letters for the Etruscan aspirated row. While in the case of labials and velars, this transition appears to have happened smoothly (Pi = /p/, Phi = /b/; Kappa = /k/, Khi = /g/), the characters for the dentals were shifted around. *Es 120 clearly demonstrates the use of Tau for /d/; the abovementioned Chiusi-style Theta ![]() (

(![]() in Es 1 and *Es 122) must be expected to stand for /t/. This distribution is also documented for phase 2 Vicenza on a stela (Vi 2). In the younger Este alphabet (and also in the sanctuaries of Làgole (Calalzo di Cadore) and Auronzo di Cadore), /t/ as in the archaic inscriptions is written as a (large) St. Andrew's cross, but Zeta is employed to write /d/. A third combination is used in Padua, where first Etruscan Tau, later St. Andrew's cross are in use for /d/, while /t/ is written with a more traditional framed form of Theta

in Es 1 and *Es 122) must be expected to stand for /t/. This distribution is also documented for phase 2 Vicenza on a stela (Vi 2). In the younger Este alphabet (and also in the sanctuaries of Làgole (Calalzo di Cadore) and Auronzo di Cadore), /t/ as in the archaic inscriptions is written as a (large) St. Andrew's cross, but Zeta is employed to write /d/. A third combination is used in Padua, where first Etruscan Tau, later St. Andrew's cross are in use for /d/, while /t/ is written with a more traditional framed form of Theta ![]() (rounded or angular).

(rounded or angular).

The origin of St. Andrew's cross is somewhat obscure: Prosdocimi (p. 332), regarding the archaic distribution, explains Tau for /d/ and Theta for /t/ by a developing homography of ![]() and

and ![]() /

/ ![]() . The phonetic values were swapped before the characters were differentiated again, leading to

. The phonetic values were swapped before the characters were differentiated again, leading to ![]() being used for /t/ henceforth. He points to the Lepontic alphabet and the Este alphabet tablets for evidence of a tendency of Tau to tend towards a cross-shape. To further avoid homography in this area, Tau was substituted by Zeta in Este; in Padua, the form of Theta was changed to

being used for /t/ henceforth. He points to the Lepontic alphabet and the Este alphabet tablets for evidence of a tendency of Tau to tend towards a cross-shape. To further avoid homography in this area, Tau was substituted by Zeta in Este; in Padua, the form of Theta was changed to ![]() (note that the variety of Theta used in Padua was the standard form in Chiusi, not Veii, as Prosdocimi asserts; see table), which allowed Tau to turn into

(note that the variety of Theta used in Padua was the standard form in Chiusi, not Veii, as Prosdocimi asserts; see table), which allowed Tau to turn into ![]() . In other words, according to Prosdocimi,

. In other words, according to Prosdocimi, ![]() has two separate origins. On the Este writing tablets, where the letters can be unambiguously identified by their position in the row, Tau appears – with Prosdocimi: is retained as a lettre morte – in the shape of a cross, similar to, but clearly distinct from, Theta: While the latter is a large

has two separate origins. On the Este writing tablets, where the letters can be unambiguously identified by their position in the row, Tau appears – with Prosdocimi: is retained as a lettre morte – in the shape of a cross, similar to, but clearly distinct from, Theta: While the latter is a large ![]() , Tau is smaller and sometimes lopsided (e.g. in Es 23, see table). The individual letters being written in rectangular fields formed by a grid, with the grid lines regularly being used as hastae, it has been argued that the entire frame around the St. Andrew's cross representing Theta, whose tips reach into the corners of the field, is supposed to be part of the letter, forming a large, but otherwise inconspicuous

, Tau is smaller and sometimes lopsided (e.g. in Es 23, see table). The individual letters being written in rectangular fields formed by a grid, with the grid lines regularly being used as hastae, it has been argued that the entire frame around the St. Andrew's cross representing Theta, whose tips reach into the corners of the field, is supposed to be part of the letter, forming a large, but otherwise inconspicuous ![]() . Theta would then have come to be reduced to only the cross through reinterpretation. This explanation, however, predating Prosdocimis distinction of older and younger Venetic alphabet, does not account for the early appearance of

. Theta would then have come to be reduced to only the cross through reinterpretation. This explanation, however, predating Prosdocimis distinction of older and younger Venetic alphabet, does not account for the early appearance of ![]() and its apparent connection with Chiusi; note also that of six preserved tablets, a third (Es 24 and Vi 3) lack grid lines and yet feature Theta without a frame. On Es 25, where the grid lines are not used as parts of the letters, Theta is missing due to object damage, but the tablet serves to corroborate Prosdocimis theory by having Zeta in the place of Tau, probably due to a scribal error.

and its apparent connection with Chiusi; note also that of six preserved tablets, a third (Es 24 and Vi 3) lack grid lines and yet feature Theta without a frame. On Es 25, where the grid lines are not used as parts of the letters, Theta is missing due to object damage, but the tablet serves to corroborate Prosdocimis theory by having Zeta in the place of Tau, probably due to a scribal error.

The Venetic script features Omikron, which in the younger Este alphabet is situated not in its ancestral place, but at the very end of the row, as evidenced by the votive tablet Es 23, the only one bearing a complete row (in addition to the usual consonant-only). While Omikron is usually assumed to have been acquired directly from the Greek alphabet, probably through contact with Greeks settling in and south of the Po delta, Prosdocimi (p. 329) favours the theory that it was taken as a lettre morte (through writing instruction) from the Etruscan alphabet before its ultimate reduction. The Venetic use of Sigma vs. San follows the South Etruscan use, Sigma being the character used for the default sibilant and San leading a marginal existence. This is also the case in the archaic inscriptions; for possible explanations see Prosdocimi on p. 330 f. Finally, one of the distinctive features of the Venetic script is the frequent inversion of Lambda and Upsilon.

Raetic

The Raeti (find places in green on the map) appear to have learned the art of writing from the Veneti rather than the Etruscans (Schumacher 2004: 312–316). While Raetic inscriptions are only known from the 5th century onward, at a time when Etruscan inscriptions have appeared in the very North (see above), some features of the Raetic script strongly suggest a Venetic source.

1. Employment of Phi, Khi and Tau for mediae or phonemes interpreted as mediae by Indo-Europeans (see below).

2. St. Andrew's cross for /t/.

3. Non-employment of Zeta: Raetic, like Etruscan, had a dental affricate /z/ (or similar). While Etruscan used Zeta to write this phoneme, Raetic inscriptions feature two graphically distinct special characters, which appear to have been newly created. The fact that Zeta was not used to write /ts/ in Venetic can explain this discontinuity.

4. Rudimental syllabic punctuation.

5. Orientation of Upsilon.

As in Venetic, different alphabet variants are used for writing the Raetic language. However, the use of characters for dentals, though not completely uniform, is not conflicting. St. Andrew's cross, the most prevalent character for a dental, is in use throughout the Raetic realm, and may be expected to primarily write t. Tau is much rarer and not employed in the epigraphically prolific central area (Sanzeno alphabet), but can be demonstrated to write ~d in Magrè and Steinberg. The Raetic alphabets are therefore closest to the Archaic Venetic alphabet, but the appearance of (somewhat idiosyncratic) syllabic punctuation in some places indicates an acquaintance with a phase 2 Venetic source. The most suitable candidate, unfortunately represented by only three documents, is Vicenza: The lengthy inscription Vi 2 demonstrates the archaic use of use of ![]() and

and ![]() ; all three testimonies have Mu with three bars, typical for Raetic, instead of four. It can of course not be excluded that different Venetic varieties have influenced the Raetic script.

; all three testimonies have Mu with three bars, typical for Raetic, instead of four. It can of course not be excluded that different Venetic varieties have influenced the Raetic script.

Western Transpadania

While, in the East, language groups and script provinces can, save a couple of problematic exceptions, be brought into correspondence surprisingly well, the situation west of the river Adige is less evident.

Lepontic / Cisalpine Gaulish (Lugano alphabet)

Inscriptions in a Cisalpine Celtic language begin to appear in Western Transpadania around 600. The Lepontic core area lies between the Lago di Como and the Lago Maggiore; on the Celtic presence south of the Alps and the distinction between Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish see Uhlich 1999 and 2007. The inscriptions are collected in the Lexicon Leponticum, including all testimonies which may contain Celtic language material, as well as all inscription finds from west of the Adige even if ascription is dubious: A considerable number of documents, mostly short/fragmentary inscriptions of a low date, cannot be shown to be linguistically Celtic, or even to be written in the so-called Lugano alphabet (find places in brown on the map). The "Lepontic" corpus being accordingly large and varied, it is hard to determine how the usual schibboleth characters – those for stops and fricatives – are used. Pi, Kappa and St. Andrew's cross are the standard letters, and can be shown to be used for both tenues and mediae. While Phi does not occur at all, Khi is employed for /g/ in one of the oldest inscriptions, as well as in three younger ones (TI·13, PV·4, VC·1.2) and in coin legends (NM·6.1, NM·6.1). In the latter, Khi appears together with Theta addΘ6 s in the name Segetu or Segedu, which is also attested on four ceramic bowls from Prestino – here with Kappa for /g/ and Zeta ![]() for the dental. Theta appears two more times, in the shape

for the dental. Theta appears two more times, in the shape ![]() , in old VA·3 (possibly Etruscan) and the Inscription of Prestino. The lengthy inscription on a stela is the only Lepontic text in which a systematic use of the characters for dentals can be observed: St. Andrew's cross is absent, Theta appears to stand for /t/. Tau in the shape

, in old VA·3 (possibly Etruscan) and the Inscription of Prestino. The lengthy inscription on a stela is the only Lepontic text in which a systematic use of the characters for dentals can be observed: St. Andrew's cross is absent, Theta appears to stand for /t/. Tau in the shape ![]() demonstrably stands for /d/, while Zeta

demonstrably stands for /d/, while Zeta ![]() represents the affricate. Pi and Kappa are used for /p/ and /g/. Tau appears twice in later inscriptions (TI·36, NO·21.1), both times in the shape

represents the affricate. Pi and Kappa are used for /p/ and /g/. Tau appears twice in later inscriptions (TI·36, NO·21.1), both times in the shape ![]() , and both times together with St. Andrew's cross. While this strongly suggests that Lepontic St. Andrew's cross must, like its Venetic equivalent, be identified with Theta, the combined use of the two characters cannot be shown to be systematic (/t/ vs. /d/). Tau-, Zeta- and Khi-like shapes crop up a number of times in dubious and/or uninstructive contexts (see LexLep); another instance of lexical use of Zeta in NM·16. Beta, Delta and Gamma are absent until the appearance of Latin(oid) inscriptions from the Roman imperial time, but Omikron is present from the earliest inscriptions. On the use of San see LexLep and Stifter 2010.

, and both times together with St. Andrew's cross. While this strongly suggests that Lepontic St. Andrew's cross must, like its Venetic equivalent, be identified with Theta, the combined use of the two characters cannot be shown to be systematic (/t/ vs. /d/). Tau-, Zeta- and Khi-like shapes crop up a number of times in dubious and/or uninstructive contexts (see LexLep); another instance of lexical use of Zeta in NM·16. Beta, Delta and Gamma are absent until the appearance of Latin(oid) inscriptions from the Roman imperial time, but Omikron is present from the earliest inscriptions. On the use of San see LexLep and Stifter 2010.

Pi and Lambda are distinguished systematically as ![]() vs.

vs. ![]() ; Upsilon appears tip-down

; Upsilon appears tip-down ![]() , though inverted forms

, though inverted forms ![]() do occur. Alpha is closed (A19 s and similar) in the older inscriptions, later changing into

do occur. Alpha is closed (A19 s and similar) in the older inscriptions, later changing into ![]() . idg sprache - schwer zu sagen ob innovationen von venetisch oder unabhängig, v.a. wenn vorbild auch chiusi (p, l)

. idg sprache - schwer zu sagen ob innovationen von venetisch oder unabhängig, v.a. wenn vorbild auch chiusi (p, l)

Verger 1998 argues for a transmission of the alphabet to Western Transpadania via the area of Genova and the Scrivia valley. Note that a number of inscriptions from the area of La Spezia / Massa-Carrara displayed as Etruscan on the map are filed as linguistically and/or epigraphically Celtic / North Italic in the LexLep (sigla MS and SP).

Camunic (Sondrio alphabet)

The corpus of the so-called Sondrio alphabet ("Camunic script“), conspicuous for its obvious graphic peculiarities, comprises the rock inscriptions of the Valcamonica, and a handful of testimonies from other places whose characters bear resemblance to those of the rock inscriptions, though the alphabets cannot be said to be identical (find places in grey on the map). Indeed, different systems seem to have been employed in the Valcamonica itself. The sigla system is not standardised, but useful collections are provided by Mancini 1990 and Tibiletti Bruno 1990. The language written in the rock inscriptions, called "Camunic" after the demonym Camunni documented by the ancients, has not yet been deciphered or convincingly connected to any of the surrounding languages; the other testimonies have been argued to write diverse languages: While the two inscriptions on stelae from Montagna in Valtellina (PID 252) and Tresivio (PID 253) feature endings similar to those commonly found in Camunic rock inscriptions, the non-Latin part of the Voltino bilingua has been read Etruscan as well as Raetic and Celtic. Celtic has also been suggested for the inscription on the Castaneda flagon, datable to the 5th–4th c. The dubious inscription AV-1, included in the TIR as linguistically Raetic, appears to be written in a variant of the Sondrio alphabet. Finally, the fragmentary inscription on a stela from Cividate Camuno in the Valcamonica itself is utterly enigmatic.

The main problem about the reading and interpretation of the inscriptions lies in the identification of the letters: Rock inscriptions from different localities, alphabetaria, and the (possibly idiosyncratic) testimonies from abroad appear to exhibit substantial differences in the use of some characters, which could so far be neither conclusively sorted out individually, nor reconciled. The picture presented by the twelve alphabetaria, or fragments of such (first edited in Tibiletti Bruno 1990; see also Tibiletti Bruno 1992), from the Valcamonica in particular demonstrates the Sondrio alphabet to be the odd one out among the North Italic alphabets. The table shows the characters as they appear in two distinct groups of alphabetaria: The first line gives the alphabet row PC 10 from Piancogno, with letters slightly standardised where their shape deviates from Camunic standard (Nu, Qoppa). The positions of Mu and Nu as well as of Gamma and Delta are interchanged in the original, Delta being written in ligature with Beta (sharing its last hasta). The ligature and possibly the inversion of the nasals also occur in the very similar row PC 27. The other alphabetaria or fragments of such from Piancogno are PC 6, PC 12 and probably PC 28. The second line gives an ideal alphabetarium from rock 24 of the Foppe di Nadro, based on FN 3, FN 4, FN 5 and FN 6, where only FN 3 and FN 6 are complete. Here also the nasals are interchanged. The two other alphabet fragments FN 1 and FN 2, also on rock 24, both end with Digamma (?) and display a variant form of Gamma ![]() . The presence of a complete Greek row suggests that the Sondrio alphabet came to Transpadania directly from a Greek source, without Etruscan mediacy. More than that, the Greek model can be argued not to have been of the "red" variety like the Euboic alphabet from which the other Italic alphabets ultimately derive. Even under such a premise, the shapes of the letters are highly unusual, not to mention the question of how such a script could have found its way into the remote Oglio valley.

. The presence of a complete Greek row suggests that the Sondrio alphabet came to Transpadania directly from a Greek source, without Etruscan mediacy. More than that, the Greek model can be argued not to have been of the "red" variety like the Euboic alphabet from which the other Italic alphabets ultimately derive. Even under such a premise, the shapes of the letters are highly unusual, not to mention the question of how such a script could have found its way into the remote Oglio valley.

There are two notable similarities between the Camunic and Raetic corpora, i.e. that both graphic variants of the Raetic special character appear in the context of the Sondrio alphabet: The character taking the position of San in PC alphabetaria is reminiscent of the Magré special character ![]() /

/ ![]() (but note that Magré has standard San); an arrow-shaped character like the Sanzeno special character

(but note that Magré has standard San); an arrow-shaped character like the Sanzeno special character ![]() appears in the problematic end sequences of the PC alphabetaria and on the Castaneda flagon.

appears in the problematic end sequences of the PC alphabetaria and on the Castaneda flagon.

Table

| Nestor's Cup | 725–700 | ← | A19 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyme 2 (alphabetarium) | 700–675 | → | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AV 9.1 (alphabetarium) | ~650 | ← | addKsi1 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clusium (statistical) | 7th–6th c. |

← | A19 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archaic Venetic | 6th c. | ← | A19 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portonaccio (statistical) | 6th c. | ← | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Es 23 (votive plaque) | ?? | ← | [ |

[ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cadore | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Padova | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vi 2 | ?? | ← | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magrè alphabet (standardised) | ← | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sanzeno alphabet (standardised) | ← | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CO·48 (stela) | ~500 | ← | addSan3 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NO·21.1 (gravestone) | ~100 | → | addSan4 s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PC 10 (alphabetarium) | ?? | → | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Foppe di Nadro (alphabetaria) | ?? | ← | addKsi2 s |

Map

Raetic script

The Raetic alphabets

Linguistically Raetic inscriptions are written in two alphabets. These alphabets differ from each other in the use of graphic variants of a handful of letters, but share certain features which set them apart from the other North Italic alphabets and can therefore be considered typically Raetic. They are traditionally named after the most important find places, i.e. Magrè and Sanzeno. The latter was formerly termed "Bolzano alphabet" after some early finds from the area; Sanzeno has replaced Bozen as the eponymous site after the discovery of the sanctuary with its numerous votive inscriptions.

| Pi | Lambda | Upsilon | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magrè alphabet | |||

| Sanzeno alphabet |

Pi, Lambda and Upsilon are the schibboleth characters which primarily distinguish the Magrè and Sanzeno alphabets. The Magrè alphabet employs Venetoid forms: Pi with an angle ![]() (sometimes opened

(sometimes opened ![]() or similar), Lambda with a bar on top

or similar), Lambda with a bar on top ![]() , Upsilon tip-up

, Upsilon tip-up ![]() . The Sanzeno alphabet bears a closer resemblance to the Lugano and Etruscan alphabets: tip-down Upsilon

. The Sanzeno alphabet bears a closer resemblance to the Lugano and Etruscan alphabets: tip-down Upsilon ![]() and Lambda with the bar on the bottom

and Lambda with the bar on the bottom ![]() correspond to the forms in those groups. Pi, however, is redundantly marked by its simple bar extending from the hasta against writing direction

correspond to the forms in those groups. Pi, however, is redundantly marked by its simple bar extending from the hasta against writing direction ![]() . The two systems are never mixed (e.g.

. The two systems are never mixed (e.g. ![]() co-occurring with

co-occurring with ![]() ); the only possible case of overlap or interference is ←

); the only possible case of overlap or interference is ←![]() /

/ ![]() → in Sanzeno context (see P for details and discussion). While the forms of Pi, Lambda and Upsilon clearly connect the Magrè alphabet with the Venetic alphabets, it is unclear whether the peculiarities of the Sanzeno alphabet are due to influence from Western Transpadania or even Etruria.

→ in Sanzeno context (see P for details and discussion). While the forms of Pi, Lambda and Upsilon clearly connect the Magrè alphabet with the Venetic alphabets, it is unclear whether the peculiarities of the Sanzeno alphabet are due to influence from Western Transpadania or even Etruria.

In addition to the abovementioned ones, two other letters appear consistently in different graphic variants in the two alphabets. Heta, though not common, always features three bars ![]() in Magrè context, but two

in Magrè context, but two ![]() in Sanzeno context (

in Sanzeno context (![]() is as yet undocumented). The Raetic special character has the form

is as yet undocumented). The Raetic special character has the form ![]() in Sanzeno context (not only in Sanzeno itself), whereas it appears as

in Sanzeno context (not only in Sanzeno itself), whereas it appears as ![]() exclusively in Magrè, being otherwise absent from Magrè-type inscriptions. Furthermore, some letters are exclusive to one of the alphabets: If the relevant letters in NO-17 are read Pi, Tau does not occur in Sanzeno context. The use of the character Φ5 s appears to have been even more restricted (see Φ), but might be argued to be tied to the Magrè alphabet. Lastly, vestiges of Venetic syllabic punctuation are found only in Magrè context.

exclusively in Magrè, being otherwise absent from Magrè-type inscriptions. Furthermore, some letters are exclusive to one of the alphabets: If the relevant letters in NO-17 are read Pi, Tau does not occur in Sanzeno context. The use of the character Φ5 s appears to have been even more restricted (see Φ), but might be argued to be tied to the Magrè alphabet. Lastly, vestiges of Venetic syllabic punctuation are found only in Magrè context.

The most prominent feature unifying the Raetic alphabets is a negative one: the absence of Omikron. Seeing as it is linguistically motivated, it does not provide a strong argument for the epigrahical correlation of the two groups. Purely epigraphical characteristics connecting the two are ![]() with only three bars, as well as two characteristics pertaining to writing direction: ←

with only three bars, as well as two characteristics pertaining to writing direction: ←![]() with the bar slanting downwards against writing direction, and ←

with the bar slanting downwards against writing direction, and ←![]() with the upper angle opening against writing direction. Both the latter features are prevalent in Magrè context, and almost exclusive in Sanzeno context.

with the upper angle opening against writing direction. Both the latter features are prevalent in Magrè context, and almost exclusive in Sanzeno context.

The areas in which the Magrè and Sanzeno alphabets are used are neatly separated: Magrè-type inscriptions come from the South and the North of the Raetic realm, more precisely the valleys of the Alpine foothills connecting the area of Trento with the Padan plain, and the Wipp, Puster and Inn valleys of North Tyrol plus the Northern Limestone Alps. The Sanzeno alphabet is used in the central area, i.e. the Nonsberg, the upper Etsch valley (including the Unterland and the Vinschgau) and the Eisack valley, with tributary valleys and the surrounding highlands.

Inscription finds and subcorpora

Magrè alphabet – South

- Castelcies (TV): The stone slab is of ultimately unknown provenance. Filed as written in the Magrè alphabet, with Raetic Mu and Alpha, but

→. Linguistically, not indubitably Raetic. The Latin text on the reverse side, unfortunately, appears to have nothing to do with the North Italic inscription.

→. Linguistically, not indubitably Raetic. The Latin text on the reverse side, unfortunately, appears to have nothing to do with the North Italic inscription. - Padova (PA): PA-1 (not autopsied)

- area of Verona (VR): VR-1–VR-5 (not autopsied)

- San Giorgio di Valpolicella (not autopsied)

- Trissino (TR): TR-1–TR-4 (not autopsied)

- Magrè (MA): MA-1–MA-24 (not autopsied)

- Val d'Astico (AS): AS-1–AS-14 (not autopsied)

- Montesei di Serso (SR): Twelve pieces of antler, found together in a house and bearing Raetic inscriptions at least partly similar in form and content, appear to testify to the presence of a Raetic sanctuary. The inscriptions are written in the Magrè alphabet; only SR-2 has

, not accompanied by Pi or Lambda, but ←

, not accompanied by Pi or Lambda, but ← and – apparently – syllabic punctuation. ←

and – apparently – syllabic punctuation. ← and ←

and ← both occur (4:7), though never in the same text; equally, Sigma is turned in both directions (in about equal distribution), once in the same inscription. Both Magrè-Heta

both occur (4:7), though never in the same text; equally, Sigma is turned in both directions (in about equal distribution), once in the same inscription. Both Magrè-Heta  and Khi (

and Khi ( ,

,  ) appear twice.

) appear twice.  is the only letter for a dental employed in Serso; Tau, Zeta and the special character are absent. Pi

is the only letter for a dental employed in Serso; Tau, Zeta and the special character are absent. Pi  occurs only once, accompanied by traditionally shaped Phi

occurs only once, accompanied by traditionally shaped Phi  , which is also found in the deviant SR-2 (

, which is also found in the deviant SR-2 ( ). Three of the other inscriptions contain the word perisna written with Φ5 s in the anlaut, on which see Φ. Seven of the twelve inscriptions feature some sort of punctuation, three of those have punctuated letters, which is singular in Raetic context (more on punctuation below). In addition to the antler pieces, three objects with non-inscriptions were found.

). Three of the other inscriptions contain the word perisna written with Φ5 s in the anlaut, on which see Φ. Seven of the twelve inscriptions feature some sort of punctuation, three of those have punctuated letters, which is singular in Raetic context (more on punctuation below). In addition to the antler pieces, three objects with non-inscriptions were found.

Sanzeno alphabet

- Caslir (CE): An old finding, the Situla di Cembra with its five sequences of letters remains the only inscribed object from the Val di Cembra. While some of the sequences may belong together, they cannot all be regarded as part of only one inscription. The alphabet, however, is consistently that of Sanzeno (exclusively ←

, ←

, ← , ←

, ← , ←

, ← ), with the exception of Pi, which occurs only once, appearing as ←

), with the exception of Pi, which occurs only once, appearing as ← . See P for details.

. See P for details. - Fleimstal / Val di Fiemme (FI)

- Sanzeno (SZ)

- Non valley (NO)

- Bozen / Bolzano area (BZ)

- Vinschgau (VN)

- Piperbühel (RN): From the site near Klobenstein / Collalbo come three inscriptions on completely different objects, which do not appear to have anything in common beyond the find place. For the inscription on a slab see below (sub "Inscriptions on stones"); the lengthy text on a wooden rod is utterly mysterious. Both are written in the Sanzeno alphabet. The third is an inscriptoid on pottery which can be compared with finds from the Eisack and Non valleys (see the inscription page).

- Rungger Egg (SI): Of the numerous pot sherds with incised marks found on the site, only two bear characters which may be referred to as letters. The similarity might, however, well be fortuitious. No certain script material is known from the area.

- Eisack valley, Mellaun / Meluno (WE): Four potsherds with marks, at least two – possibly all four – from the Reiferfelder. WE-6 and WE-7 can be compared with marks on ceramic fragments from elsewhere in the Raetic realm. No secure testimonies of script from the site.

- Eisack valley, Stufels (WE): Two objects with lengthy inscriptions. WE-3 on an isolated piece of antler (apparently originally an actual handle) is written in the Sanzeno alphabet. WE-4 is written in the Magrè alphabet, but the support – a Roman-style olla – might be imported from the South.

- Slovenian helmets (SL)

Magrè alphabet – North

- Puster valley (PU)

- Wipp valley (WE)

- Inn valley (IT)

- Ardez (EN): The only piece of inscribed pottery from the Engadin, of dubious ascription (see the inscription page).

Rock inscriptions

Petrographs from the Raetic area and displaying linguistically Raetic features have been found (so far) only in the very North, i.e. in the Northern Limestone Alps. The Schneidjoch (ST, one rock) and the site of the Achenkirch inscriptions (AK, min. two rocks) are located close to each other in the Steinberg/Achensee region (Tyrol); the Unterammergau inscriptions (UG, min. three rocks) are found in Southern Bavaria. Not all of the inscriptions registered in the TIR are epigraphically or linguistically utilisable – of some, only faint traces can be seen, many are doubtful, a few are most probably not Raetic or even script. Among the longer testimonies from Tyrol, two groups emerge under both alphabetical and linguistical aspects:

- Sinistroverse inscriptions ending in -nuale, containing straight-forward name formulae in the pertinentive case (where decipherable), featuring the expectable Venetoid

and other Magrè letter forms and being generally inconspicuous: ST-1, ST-2, ST-3, AK-1.1, AK-1.2, AK-1.6, AK-1.7, AK-1.19.

and other Magrè letter forms and being generally inconspicuous: ST-1, ST-2, ST-3, AK-1.1, AK-1.2, AK-1.6, AK-1.7, AK-1.19. - Dextroverse inscriptions of unclear linguistic content, showing certain special features (to varying extent): the punctuation of suffixes, ligatures, and the letter forms

(angles opening in writing direction),

(angles opening in writing direction),  and

and  . Of these inscriptions, ST-5 (the only sinistroverse one) and ST-6 are particularly similar in structure; AK-1.11 (as well as the fragmentary AK-1.10, AK-2.1 and AK-2.2) may be grouped alongside. Dextroverse AK-1.17 lacks the punctuated suffixes, but has

. Of these inscriptions, ST-5 (the only sinistroverse one) and ST-6 are particularly similar in structure; AK-1.11 (as well as the fragmentary AK-1.10, AK-2.1 and AK-2.2) may be grouped alongside. Dextroverse AK-1.17 lacks the punctuated suffixes, but has  and apparently a (different) ligature.

and apparently a (different) ligature.

For a detailed itemisation see the table on the right. The inscriptions ST-4 and ST-8 do not fit in smoothly with either group. The testimonies from Unterammergau are hard to compare with the Achental-subcorpus: Of the two utilisable inscriptions, both dextroverse, UG-1.1 is unusually short and features ![]() ; UG-1.2 has standard

; UG-1.2 has standard ![]() and is equally opaque.

and is equally opaque.

The inscriptions of the first group are written in the Magrè alphabet, with the typically Raetic orientation of Sigma, but "traditional" North Italic Alpha with the bar slanting down in writing direction. As concerns the second group, the form ![]() of Lambda occurs in the votive inscriptions of the Venetic sanctuaries of Auronzo and Calalzo (Làgole) di Cadore in the upper Piave/Ansiei valley, but this is the only similarity with that subcorpus. Punctuation of suffixes rather than syllabic punctuation is not known from Venetic, but see the comments on punctuation in Raetic below. The ligatures stand isolated as well. None of the Raetic petrographs show any particular affinity to the only rock inscriptions in the Venetic corpus, those from Würmlach in the Gail valley (Gt 13–23).

of Lambda occurs in the votive inscriptions of the Venetic sanctuaries of Auronzo and Calalzo (Làgole) di Cadore in the upper Piave/Ansiei valley, but this is the only similarity with that subcorpus. Punctuation of suffixes rather than syllabic punctuation is not known from Venetic, but see the comments on punctuation in Raetic below. The ligatures stand isolated as well. None of the Raetic petrographs show any particular affinity to the only rock inscriptions in the Venetic corpus, those from Würmlach in the Gail valley (Gt 13–23).

Apart from the somewhat doubtful and epigraphically Camunic AV-1, the rock inscriptions are the only testimonies of Raetic from beyond the Inn valley. Any propositions concerning the ultimate function of these inscriptions and the identity and purpose of the writers must at this point remain speculative.

Writing of dentals

Pi, Theta (St. Andrew's cross) und Kappa sind die Standard-Plosivzeichen - korrespondieren mit was im etruskischen? stefans theorie: phi, tau, khi bezeichnen lenisallophone im inlaut, im anlaut sinds lehnphoneme, und entsprechen mediae. was aber mit der aspirierten etruskischen reihe? entsprechungen?

Syllabic punctuation and word separation

Ligatures

Writing direction

Bibliography

| AIF I | Carl Pauli, Altitalische Forschungen. Band 1: Die Inschriften nordetruskischen Alphabets, Leipzig: 1885. |

|---|---|

| Colonna 1972 | Giovanni Colonna, "Clusium et Orvieto", Studi Etruschi 40 (1972), 470–471. |

| ET | Helmut Rix, Gerhard Meiser (Eds), Etruskische Texte. Editio Minor [= ScriptOralia 23-24; Reihe A, Altertumswissenschaftliche Reihe 6-7], Tübingen: Gunter Narr 1991. (2 volumes) |

| Gamper 2006 | Peter Gamper, Die latènezeitliche Besiedlung am Ganglegg in Südtirol. Neue Forschungen zur Fritzens-Sanzeno-Kultur [= Internationale Archäologie 91], Rahden/Westfalen: Leidorf 2006. |

| Jeffery 1990 | Lilian H. Jeffery, The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece. A study of the origin of the Greek alphabet and its development from the eighth to the fifth cernturies B.C., Oxford: 1990. |

| Lexicon Leponticum | David Stifter, Martin Braun, Michela Vignoli et al., Lexicon Leponticum. URL: http://www.univie.ac.at/lexlep/ |

| Lunz 1981b | Reimo Lunz, Venosten und Räter. Ein historisch-archäologisches Problem [= Archäologisch-historische Forschungen in Tirol Beiheft 2], Calliano (Trento): 1981. |

| Mancini 1980 | Alberto Mancini, "Le iscrizioni della Valcamonica. Parte 1: Status della questione. Criteri per un'edizione dei materiali", Studi Urbinati di storia, filosofia e letteratura Supplemento linguistico 2 (1990), 75–167. |

| Marchesini 2013 | Simona Marchesini, "Descrizione epigrafica della lamina", in: Carlo de Simone, Simona Marchesini (Eds), La lamina di Demlfeld [= Mediterranea. Quaderni annuali dell'Istituto di Studi sulle Civiltà italiche e del Mediterraneo antico del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Supplemento 8], Pisa – Roma: 2013, 45–53. |

| Marinetti 2004 | Anna Marinetti, "Nuove iscrizioni retiche dall'area veronese", Studi Etruschi 70 (2004), 408–420. |

| Marinetti 2004b | Anna Marinetti, "Venetico: Rassegna di nuove iscrizioni (Este, Altino, Auronzo, S. Vito, Asolo). (Rivista di Epigraphia Italica)", Studi Etruschi 70 (2004), 389–408. |